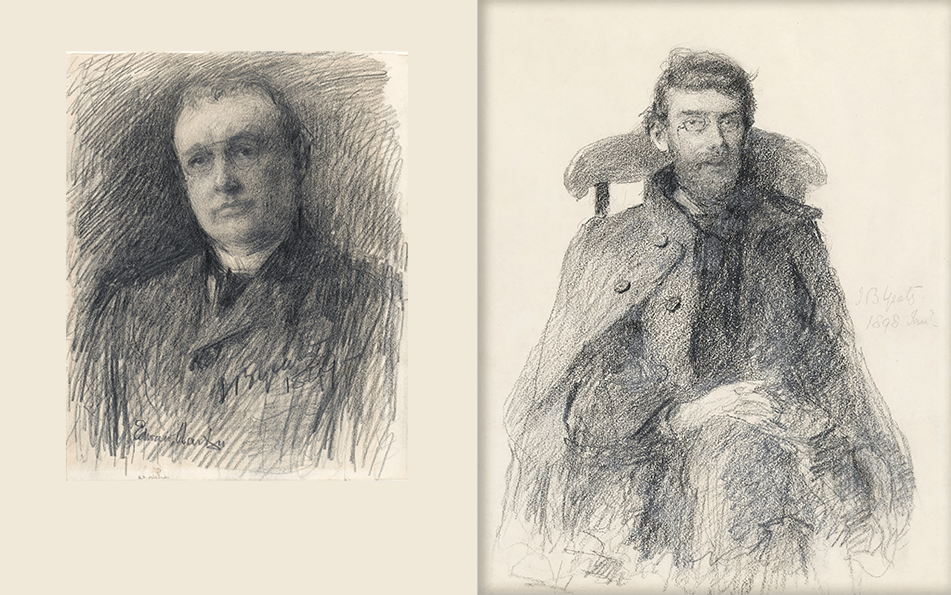

Two portraits by John Butler Yeats in the National Gallery of Ireland. On the left is Edward Martyn in 1899. A patron of the arts and author, Martyn is George Moore’s foil in Hail and Farewell! Ave (1911). On the right is George Russell in 1898. An artist and author who used the pseudonym Æ, Russell is Moore’s foil in Hail and Farewell! Salve (1912). These two volumes of the great trilogy are now live on GMi.

A Book for George

Last month I enthused about Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. The exhibition epitomizes art during George Moore’s formative years without mentioning him. (He studied painting in Paris in 1874, but was 22 years old and hadn’t cracked his shell.)

Today I’m enthusing about Anka Muhlstein’s The Pen and the Brush (2017). Like the exhibition, her book helps me see George’s emergent aestheticism in shimmering context!

She doesn’t seem to mention George Moore (I’m not sure because the book is not indexed). Moreover she opens with an erroneous claim that “In England, [Virginia] Woolf would be the first to write about the influence painting had on literature.”

Nonetheless The Pen and the Brush is a marvelous account of reciprocity between nineteenth century painters and novelists, starting with the beloved Balzac and including other French writers who incubated George Moore and got him to hatch.

Consider reading the exhibition catalog and The Pen and the Brush together!

Who Can’t Read Books?

Also on the subject of reading, the New York Times recently published a review of Herscht 07769, a novel by László Krasznahorkai translated from the Hungarian into unreadable English.

The Hungarian original may also be unreadable; I don’t know about that. My mother was Hungarian but didn’t teach me her native language. Csak angolul beszélek.

I haven’t read Herscht 07769, yet I know it’s unreadable because its 400 insane pages consist of a single sentence. László may be emulating Jimmy, the Irish genius who wrote famously unreadable novels a hundred years ago and who purportedly said, “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.”

Setting aside the pedagogical question, who cares what he meant? we may wonder if ensuring one’s immortality is a priority, or even the business, of a novelist? If you’re a professor, perhaps you think it is. Your job is explaining enigmas and puzzles to kids and colleagues.

Others like myself think not. The priority and business of a novelist, from my point of view, is to delight and edify, in that order. Meaning the right to edify is earned with a passage through delight.

Readers may be delighted and edified by many different literary things (for me it’s the prose of George Moore). Nonetheless, I’m pretty sure that a 400-page sentence ain’t one of them.

Rose Horowitch in The Atlantic indirectly reinforced my view in her essay about “Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books.”

We know that college English studies have been a slow moving train wreck for half a century. Now adding to its chronic woes, according to Rose, is the discovery that undergraduates cannot, and don’t want to, read immortal texts that were written for their teachers; texts that have to be explained to be understood; texts that have to be studied to be enjoyed; texts that meander for countless pages without a period or paragraph break.

Experts suggest that this new problem may be caused by technology, or by mentally limited readers, or anything other than the texts themselves. Thus they recognize the symptoms of educational decadence, but I suspect that they miss the cause.

And what else can we expect when Garth Risk Hallberg, the author of that Times book review, ranks László as a “master” and László’s novels as bona fide “masterpieces.”

Thanks perhaps to James Joyce and his acolytes, the unreadable often feels like the acme of serious literary publishing; befuddlement is the bar to which serious novelists aspire in order to ensure their immortality.

George Moore did not aspire to immortality. He did not try to confuse readers and he didn’t care about professors one way or another. His artistic goals were to delight and edify, in that order.

Why George?

I recently started my first Gofundme Campaign. The purpose is worthwhile, the goal is modest and attainable. So say I!

Donors will share credit for bringing an important part of a fine writer’s canon out of the analog crypt, into our world of art and literature, and back to life (digitally).

After launching the Campaign I decided to use my voice and face to do some of the asking. I drafted the video script that I’m sharing below.

The script may change before the camera rolls, but if you approve the draft — your donation is always welcome.

The Script

I met George Moore nearly forty years after he died.

Not George in the flesh, of course.

I met his legacy as a venerable and eclipsed man of letters.

I started reading his novels and stories, then memoirs, then plays and poems, then essays, and even read his bibliography line by line.

Finally I read some of the unpublished letters he wrote to friends and family and many others.

And I was smitten.

My reading for pleasure morphed into research.

Research morphed into editing.

Editing morphed into publishing.

(I’ve overlooked collecting — about 500 volumes so far!)

On and off for about 50 years, George has been a friend.

Actually more than a friend.

He grounded and centered me as I matured and changed.

Even when I changed almost beyond recognition, he held a mirror that showed who I am.

Ironically I guess, this transformative and contrarian author has been my compass and safe harbor.

He inspired a pastime, a vocation, a hobby, and ultimately a lifelong passion.

And he did all that without ever telling me why.

The question is still open: Why George?

Why have I devoted such time and resources to him?

Why should others care enough to donate?

Nobody has an economic or moral incentive, so why bother?

This question hasn’t occurred to me before now.

That may be because, by nature, I do what I want.

And rarely pause to explain why, even to myself.

But now it’s different.

When accepting donations on behalf of George, I have a duty to explain why him, and also why me?

Not because George is the greatest writer of his generation, or his tradition, or his country, or even the greatest writer I’ve read.

George isn’t “the greatest.”

Superlatives have nothing to do with him (or with me).

Rather than “the greatest,” to me he’s just sympatico.

Sympatico means I get him as easily as I breathe, and I believe he gets me in my pose as a skeptical reader.

He knows that I have zero tolerance for insincerity, or vulgarity, or triviality and foolishness, and he likes that about me.

It’s something we have in common.

As a writer, despite his flaws, he made his own life and mine more beautiful.

Not better, because better isn’t the point for somebody like George Moore.

His forte is beauty for its own sake; the proverbial gem-like flame.

This is why I’m trying to bring him back to life with technology.

And why I seek donations to get it done.

Sooner or later I want to talk with George, one-on-one.

I want meandering conversations after dinner, by his fire.

With our cats on our laps.

I also want George to have one-on-one conversations with others.

Without me as their scholarly chaperone.

Without me explaining or interpreting what he says.

Without me even present in the picture.

My helping George speak for himself may do for others what he’s done for me.

George may become as active a part of our world as I’ve been in his.

If you’re not already a fan of George Moore, this may sound off the wall.

I may come across like an old geezer who hasn’t grown up.

And that’s okay, because that’s true of me and of George too.

Both of us never outgrew our loves of art, and beauty and truth.

We’re both strivers who excelled and succeeded, and often didn’t.

We are sympatico.

We hold mirrors up to the other.

We remind the other of who we are and long to be.

And that is the “why” of George Moore.

That’s why I’m getting him ready to meet you.

If you support the Campaign, you’ll eventually meet George as he was in life, as you are in this moment.

He may not impress you as much as he impresses me.

But I think you’ll like and learn a lot from him.

About art and literature, about Irish, English and French culture, about human nature everywhere.

And more evanescent things too.

Like how to know and be true to yourself as you make your way, ever changing.

George wasn’t the best at that, but he was always true to himself, his friends and his word.

If you’re not already one of his friends, I’m offering you the chance to become one now.

By making a donation.

A Salve for the Soul

The second volume of George Moore’s autobiography Hail and Farewell! is named Salve. Along with the first volume Ave, it is now a free ebook in the GMi Shop.

All the chapters of both volumes are also posted in the Worlds pillar of this website, where they can be read, searched and commented. Ave has 104,958 words; Salve has 107,454.

I was intrigued by the way George wove his memoirs around the identities of two boon companions: Edward Martyn in Ave and George Russell in Salve.

Each man was an archetype of the Irish Literary Revival that George witnessed and joined for a time. They are foils to an author whose archetype is different, uncertain and still emerging.

Next up for GMi is the third volume of Hail and Farewell! Vale. With that, I will have placed all of George’s autobiographical writing online, in one place, in a way that is useful to human readers and tomorrow’s machine learners.

2 responses to “Why George?”

Robert, be sure to bring some of your cards to pass out at the 19th cent, tomorrow, I am sure there will be some there that are interested in your Moore work. I will introduce you to David, my condo neighbor, and speaker for tomorrow.

Jim

LikeLike

Thanks! Actually I don’t have business cards but I have some calling cards that I can bring and write on if requested.

LikeLike