Hi Reader! My study of George Moore sprouted in New York City when I was just a big kid. After graduating at New York University and taking a grand tour of faraway places, in January 1975 I hunkered down in the reading room of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, at the main branch of the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue. I was neither a student, nor a professor, nor a gainfully employed commoner; I wasn’t even self-aware. I behaved like an itinerant explorer seeking truth about the life and work of an obscure and fascinating man of letters. Without any prerequisites, training, encouragement or supervision, I launched a Nowhere Man project called The Collected Letters of George Moore. That project is now a pillar of George Moore Interactive.

This Correspondence pillar includes at least 6000 letters written by George Moore, located in places that I will identify in another pillar of George Moore Interactive named Collections. “At least 6000” because I’m sure I haven’t found all of Moore’s extant letters — and doubt I ever will. Instead I am building a digital lounge where I can share the material I’ve got, and more that will eventually surface. This dynamic Collected Letters has neither beginning, middle nor end. It has only a center that holds together the disparate parts and expands over time.

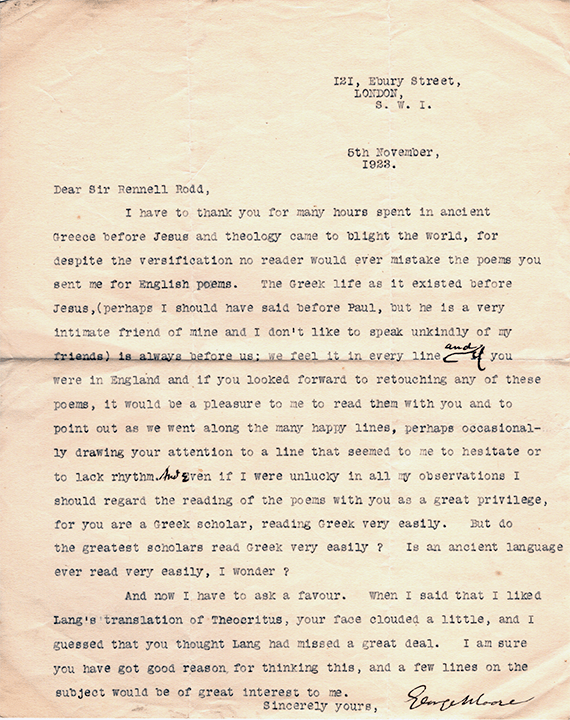

The “parts” are source materials: handwritten letters, typed letters, printed letters. By letter I mean any instance of George Moore writing what’s on his mind on a blank sheet, or letterhead, or card stock, or newsprint, and addressed to a particular individual or group. Literary letters are basically a person communicating to his friends. Moore’s last book, published just after he died, is A Communication to My Friends (1933) — and yes, according to my definition, that book is a letter and included. For similar reasons, my friend and mentor Rupert Hart-Davis included De Profundis in his Letters of Oscar Wilde (1963).

There are two ways to experience a letter. One way is to view and handle the original, tangible object (as I did at the Berg Collection and many other places). The other way is to read a printed or typed transcription. Transcribing any manuscript is a transformative process that not only makes the original writing more legible, coherent, and nowadays machine readable; it also changes the intrinsic quality of a text. Scholars and editors have argued endlessly about the give and take between these experiences: of the thing versus a representation of the thing.* For me the debate ends here and now, because George Moore Interactive presents BOTH a photographic image of each manuscript with its provenance AND a transcription in typography that is optimized for screens. Isn’t it amazing, what’s feasible when paper and ink are excluded from the publishing process!

The text of a transcription cannot stand alone. It has to be annotated, as you would expect; otherwise the meaning of words written in haste a hundred years ago would be elusive, to say the least. But “text” in my transcriptions does not manifest in ink. It’s hypertext that manifests in light, making each item of correspondence a container for keywords that are pregnant with context, inferences, implications, and capable of generating fresh meaning. Hypertext itself is “responsive to inquiry” as no printed page or author or editor ever was or can be. It turns Moore’s letters into an interactive system, rather than a cabinet of curiosities or the hobbyhorse of experts.

Ergo: The whole of Correspondence is greater than the sum of its parts!

Here on the threshold of engineering the dynamic system, my immediate next steps are clear:

- Scan my three-decker PhD dissertation with nearly 1000 transcribed letters. The dissertation was typed in 1979. No digital copy exists, to my knowledge. I’ll make one.

- Scan thousands more transcribed letters written after the cutoff date of my dissertation. I typed these in the 1980s from images I made of the manuscripts. Microfilm. Microfiche. Photocopy.

- Key in some number of manuscripts (hundreds? thousands?) that I imaged way back when but never got around to transcribing. Every one is documented on a handwritten notecard. The old fashioned way.

These steps will make letters of George Moore machine readable, intelligible and ready for 21st Century editorial treatment (the topic of a different post). Altogether this is an incredibly exciting prospect that’s been a very long time coming into view.

* For a peek at this debate, see my paper on “Challenges in Editing Modern Literary Correspondence” in TEXT: Transactions of the Society for Textual Scholarship (New York: AMS Press, 1981), pp. 257-270.

You’ll receive a confirmation email after entering your address and tapping Subscribe. Your subscription will be active after you confirm.

One response to “Collecting Letters”

Hi,

I was just at the Harry Ransom Center at Univerisity of Texas, Austin. They own a portrait of George Moore that my cousin, Michele Reardon, had recently posted online. The portrait is not currently on display, but with advance notice they will bring it out of storage for you to view it. The Ransom Center has a focus on writers. The woman we talked to had no knowledge of how the portrait ended up in their collection. She did a search of our grand uncle George and a whole list of books, papers, and letters he wrote to various people are also housed there. You can do a search if you are interested at this link under the UT library catalog. https://www.hrc.utexas.edu/research/ . FYI.

Sincerely,

Ginny Newkirk

LikeLike