Letters of 1895

George Moore’s extant letters of 1895 are live on GMi. More letters may eventually turn up — certainly he wrote many more — but these are what I’ve got so far.

One of the (many) nice things about publishing digitally is that new data (such as more letters) may be added instantly, at any time, and not have to wait on the vagaries of print publication.

Moreover stakeholders such as scholars and collectors, who may have fresh data, now have a digital place to put them. That’s not the old-school way of doing things. It’s a better way!

Based on a glance at the bibliographic record,1895 looks like a quiet interval for George Moore. He was basking in the critical and commercial glow of Esther Waters (1894). He had correctly predicted that novel would be his masterpiece while writing it, though it followed a long line of “not-quite” projects.

From a scholarly perspective it looks like George by 1895 was comfortably settled in his new reputation of distinguished man of letters. The contrarian rebel-producer finally got a seat in Parnassus! He published only one new book in 1895, the precious Celibates, and that was partially a redo of an earlier novel.

But the real action in 1895 was genetic rather than literary. The love affair George had started in 1893 with Maud Alice Burke, when she was 21 and he was 41, blossomed into heady adultery in April 1895, after she agreed to a loveless marriage with the improvident and financially stretched Sir Bache Cunard, 3rd Baronet. The letters show that George and Maud were enjoying sexual relations around the time their daughter, Nancy Cunard, was conceived in June 1895.

The question of George’s paternity has remained open over the years. He claimed in the 1920s that he was Nancy’s biological father; Nancy denied it in the 1950s; Maud was ambivalent; Bache was a passive cuckold, happy to have his young wife’s money, if not her loyalty, in a marriage of convenience.

Since there is no possibility of genetic testing of descendants, we shall have to believe what we choose to believe. IMHO, George Moore was, without a doubt, Nancy Cunard’s father.

Pesky Essays

At the request of Resurgam directors, last month I submitted nine “fundable” GMi projects for consideration. By fundable I mean theoretically worthy of investment by virtue of intrinsic and extrinsic values. The board recently met to discuss and choose the first project to develop.

That project is the same as one I targeted with a lame Gofundme Campaign: acquire 83 essays of George Moore uniquely stored at the British Library for the Aesthetics pillar of GMi. My Gofundme Campaign didn’t raise nearly enough money for this. Time to try again.

Once those 83 outlier essays are rounded up, digitized, edited and published, all of George Moore’s art and literary criticism will be restored to his living legacy and freely accessible to everybody who wants to read it (including machine learners).

I’m talking here about ±600 essays averaging 2,000 words apiece: around 1,200,000 words altogether. That is a huge slice of George’s output that we are restoring in the digital age, as we never could before.

The next question (of several) to decide: will I myself travel to London to curate the 83 outliers in the Reading Room of the British Library? Or will Resurgam recruit a contract laborer who lives in London to curate the outliers on my behalf? The first option incurs travel expenses but no labor costs. The second option incurs labor costs but no travel expenses.

I’ll let you know in August what we decide. Meanwhile, if you’d like to make a tax-deductible donation to the project, or provide contract labor in London, contact Resurgam with your offer.

Striving After Wind

“I have seen everything that is done under the sun, and behold, all is vanity and a striving after wind.” — Ecclesiastes 1:14 (ESV)

Much of George Moore’s autofiction of the 1880s is now live on GMi. That said, his comédie humaine stretched well beyond Mike Fletcher (1889) into his next novel Vain Fortune (1891), the novel after that Esther Waters (1894), and his collection of stories Celibates (1895).

He didn’t stop there, of course. His duology Evelyn Innes (1898) and Sister Teresa (1901), which he began writing in mid-1894, was also autofiction, but I vaguely recall that his characters and settings were all new.

(Not sure about that because it’s years since I read the duology. I’ll confirm after GMi publishes both titles later this year.)

Like the novels and memoirs that preceded it, Vain Fortune was the vision of a contrarian rebel-producer on the fringe. The novel is difficult to summarize briefly because it tells a bifurcated story, consisting of two parts that have little to do with each other.

Part the First

The first part is largely set in the Fitzrovia (Bloomsbury) neighborhood of London. The main protagonist is a middle-aged writer named Hubert Price: a clever but marginal playwright who strives to become the English Ibsen.

Hubert writes serious plays for a groundbreaking literary theater that doesn’t exist except in his imagination. There was no such a theater in London at the time. The closest Hubert got to one was a gratuitous production by actor-manager Montague Ford at the Queen’s Theatre in the West End.

Early readers of Vain Fortune would have recognized Montague Ford as a simulacrum of Herbert Beerbohm Tree, a prominent actor-manager at the Haymarket Theatre. From time to time, George Moore tried to interest Tree in his writing and ideas.

Hubert was a simulacrum of George Moore himself — at least the very large part of George’s ego that wanted to write plays.

George’s pretensions to a literary theater started long before Vain Fortune. They dated all the way back to his composition of Martin Luther (1879), which he tried (unsuccessfully) to have performed in London.

A bit later in his career, A Mummer’s Wife (1885) was not about literary theater per se, but nonetheless it was literature about theater. Still in the zone!

More recently George’s pretensions had taken the form of advocacy. He promoted André Antoine’s Théâtre Libre in Paris and co-founded J. T. Grein’s Independent Theatre in London.

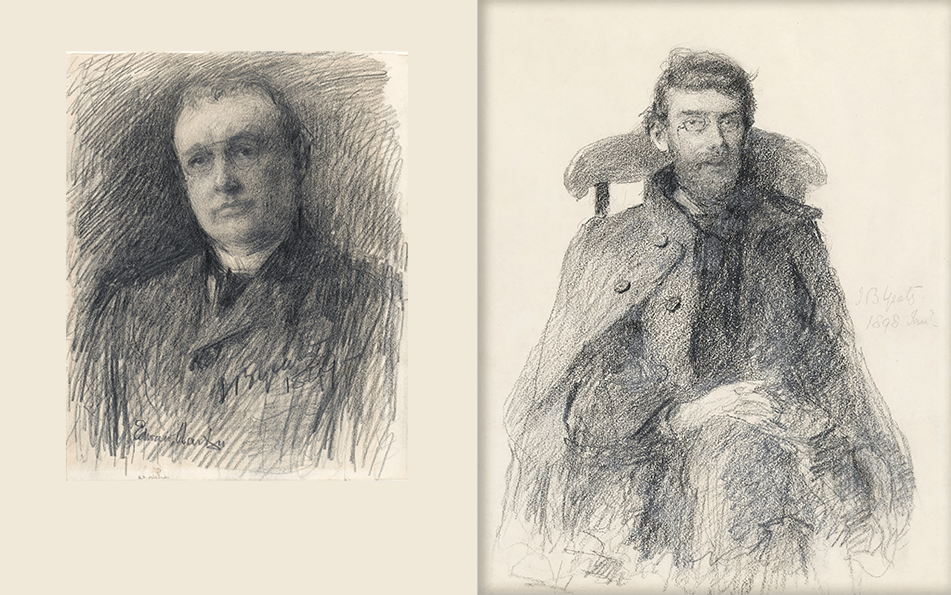

A few years hence, he would also get sucked into the Irish Literary Theatre (predecessor of the Abbey) as a co-founder with W.B. Yeats and Edward Martyn.

Though George was a skilled and moderately successful novelist and essayist, he persistently (and futilely) sought to expand his range as a playwright too. Why did he bother?

On a philosophical level, like Hubert in Vain Fortune, he wanted to reform commercial theater in London, endowing it with artistic and educational affordances. On a practical level, also like Hubert, he simply wanted to write really good plays that would fill seats and make some money.

Neither ambition was fulfilled, though this “striving after wind” was noble and culturally beneficial.

I don’t understand why George Moore the novelist and essayist wanted so badly to be a dramatist as well, but a study of Hubert Price in the first part of Vain Fortune would probably help to explain.

Hubert’s philosophy, his writing techniques, his relations with theater people, his excellent dramatic ideas that somehow failed to materialize in a script, his views of the acting profession and tastes of the public — all of this fiction reads to me like an actual conversation with George Moore as he strived for his own just-out-of-reach breakthrough dramaturgy.

For a time he thought he achieved a breakthrough with his play The Strike at Arlingford (staged in February 1893 but developed as he wrote Vain Fortune). He was disappointed, not by critical reviews, which were positive, but by his own scruples.

Part the Second

Midway through Vain Fortune the storyteller pivoted. Hubert the impoverished genius inherited the “fortune” of the novel’s title. He moved to his inherited property of Ashwood Park in Sussex, where the “vain” of the title would be worked out.

Ashwood Park is a simulacrum of Buckingham House, the beloved home of the Bridger family near Shoreham-by-Sea. We’ve been there before, under different names in previous novels, and we’ll return again in Esther Waters (1894) where it will be named Woodview.

Ashwood Park (and its other incarnations) was an idyllic country house and farm, spun into a venue for twisted ambition, quiet suffering, unrequited love, and meaningless death. Weirdness in a pastural setting!

By the way, my colleague Michael O’Shea recently visited the ruins of Buckingham House and shared his photos on GMi. Its dilapidated condition is even worse than Moore Hall, but nonetheless holy ground for readers of George. You can view some of Michael’s pictures here.

The second part of Vain Fortune is practically a different story from the first; the two are barely related, a fact the author recognized during the book’s initial publication and hastened to correct.

Vain Fortune thus became the first project in which George Moore obsessively revised his text on the proof sheets and between successive editions. From 1891 onwards, he behaved somewhat like a manic nitpicker: a potter who couldn’t bring himself to remove his formed clay from the wheel but needed to keep improving it.

Female Trouble

There is much fine writing and thematic development at Ashwood Park. The most curious and meaningful part of the novel, according to George himself, was a basket case named Emily Watson.

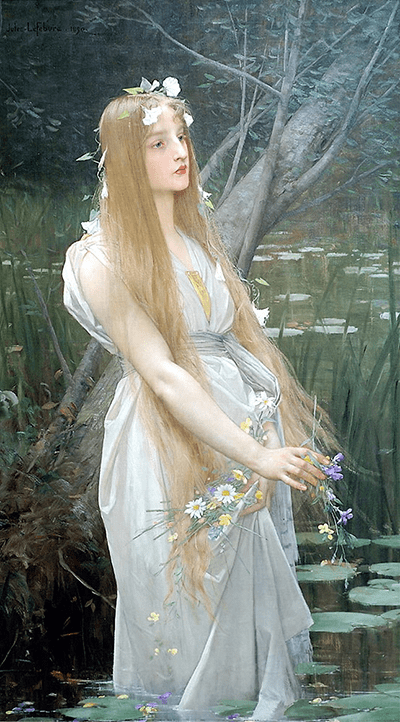

She is an extreme striver after wind, an Ophelia-like victim whose mental illness is ever present though ambiguous and just a bit out of focus.

Beautiful, desirable, intelligent, intensely sensitive, young and innocent, lacking agency, irritating, demanding, vulnerable, resentful of the male gaze: Emily is the real subject of the novel, one that the author backed into, not realizing her importance until most of the book was already written.

She is the quiet counterpoint to Rose Massey of the first part, as though George had two stories about young women to tell and didn’t know where to begin.

The more profound story in the second part of the novel is about Emily Watson and also her older companion Julia Bentley. We get an inkling of the problem in Julia’s confession:

My life has been essentially a woman’s life, — suppression of self and monotonous duty, varied by heart-breaking misfortune … You think you know the meaning of poverty: you may; but you do not know what a young woman who wants to earn her bread honestly has to put up with, trudging through wet and cold, mile after mile, to give a lesson, paid for at the rate of one-and-sixpence or two shillings an hour.

— Vain Fortune (pages 287-288)

This depressing revelation will linger in George Moore’s imagination and get resolved, less pessimistically, in Esther Waters.

For now though, all is vanity. As in the fiction that preceded it, there is no happy ending in Vain Fortune, only an unsatisfying consolation:

“Hubert!” It was Julia calling him. Pale and overworn, but in all her woman’s beauty, she came, offering herself as compensation for the burden of life.

— Vain Fortune (page 296)

Should you decide to read the first edition of Vain Fortune on GMi, remember that the book underwent significant revisions as soon as it was published (actually, even before).

Read the first edition as a draft and the editions that followed as truer expressions of the author’s intentions. The revised editions are not on GMi (yet).

Vain Fortune, complete with its lamentable Ophelia, is worth reading. You can do that chapter by chapter on GMi or download the ebook. But there is also another way…

The Third Rail of Engagement

Beyond the two regular ways to engage with Vain Fortune there is a third way which may be best of all. I call it Vain Fortune AI.

This is a PDF of the novel that you can download from GMi and upload to Google Notebook LM (or the AI assistant of your choice, though none is better than Notebook LM).

Uploading the PDF to Notebook LM will enable you to interrogate and interpret the text with machine intelligence, which sadly is greater than yours or mine; and also do some transformational things that I’ll leave you to discover.

Mind you, uploading to Notebook LM is not a substitute for reading the text (though it could be for people in a hurry). It complements reading.

Speaking metaphorically (as I have before), submitting a text to Notebook LM is comparable to turning a still image into a moving picture. The experience brings a novel to life!

Vain Fortune AI adds so much value to George Moore Interactive that I have decided to create AI versions of all the titles I previously published. I will do that over the next few weeks and continue when new titles are added.

AI versions will make it a little easier and more fun for casual readers to engage with George Moore’s literary legacy! And for scholars to investigate.

Next Up

Next month in addition to making AI versions of books on GMi, I will publish the first edition of A Modern Lover (1883).

No digital scan of this novel — George Moore’s first — is available on the Internet. Thanks to the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection at the University of Delaware Library, that’s about to change!

Beyond these two milestones, I will put George Moore’s letters of 1896 on the workbench.

From 1896 until the turn of the century, George’s love affair with “Saxon” England waned and his flirtation with “Celtic” Ireland became more and more irresistible.

Let’s follow him as he journeys to epiphany.

Bob Becker (21 July 2025)