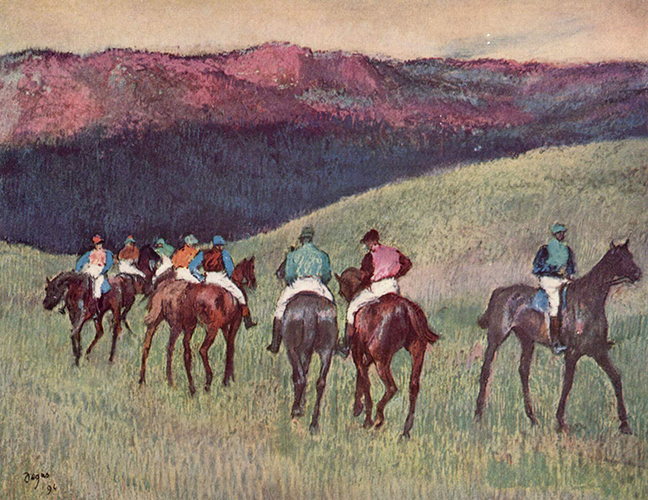

Racehorses: Training (1894), pastel on paper by Edgar Degas in the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain (Wikimedia Commons). The impressionist artist finished this landscape with racehorses around the time that his friend George Moore, after years of research and writing, published the celebrated Esther Waters (1894). There is no known connection between the picture and novel, but it looks as though Edgar visited Woodview, in the environs of Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex in order to paint the Barfield stable in the weeks before the Chesterfield Cup. “At the end of the coombe, under the shaws, stood the old red-tiled farmhouse in which Mrs. Barfield had been born. Beyond it, downlands rolled on and on reaching half-way up the northern sky.” — Esther Waters (1894, page 372). Is Silver Braid one of those mounts? Is the Demon one of those elfin riders?

Notebook LM: Go!

In last month’s newsletter, I promised to post a clean PDF of every book by George Moore published by GMi. My PDFs may facilitate the uploading of books to a generative AI application for guided analysis and interpretation.

While keeping that promise, I had to make a new Apple Book of Martin Luther (1879); what had been the last Kindle edition remaining in the GMi Shop; also the only ebook with a price higher than zero.

When I revisited my transcription of Martin Luther to make an epub, I decided this time to strip out the byzantine page layout and typography of the printed original that made it hard to use. The new ebook is now more readable by humans and machines, and the price of course is zero. Yay! (Google Docs of Martin Luther are unchanged.)

Every book transcribed so far for the Aesthetics pillar and Worlds pillar of GMi now has a downloadable PDF on its menu page. Every new book that is added to the site gets the same treatment, starting today with Esther Waters.

I am recommending Google’s Notebook LM as a superb AI research assistant, but you can use the PDFs with any AI application you like. You have options, but please don’t stubbornly resist the call of AI!

Generative AI is scary-good. It’s the fast-approaching future of textual analysis and literary criticism, not to mention pedagogy in the humanities. And there is no better way to use AI than as a very smart crowbar on the literary treasure chest of George Moore.

Revving the Search Engine

This section of the newsletter is about the mechanics of GMi — a subject of interest to practically nobody other than me. Still, it’s important and leading to a minor breakthrough. At a minimum, Bob Becker is excited!

Before I rev, please note the definitions of two keywords: page and document. The former in this context means a WordPress webpage. The latter means a Google Doc. That is what page and document mean every time I utter them.

NB. WordPress is a brand shared by WordPress.org and WordPress.com. GMi subscribes to .com’s proprietary, feature-rich authoring apps and hosting services; .com licenses .org’s open-source content-management system.

When you type georgemooreinteractive.org in a browser, WordPress.com servers sling the GMi website to your desktop or handheld device (they know the difference). I made and continue making the website with WordPress.com software.

Most GMi pages are dichotomic, meaning they’re dynamically comprised of two discrete parts:

- Part One is white text and colorful imagery on a black background. This is the page.

- Part Two is black text on a white background. This is a document that is separately published to the web and embedded in the page.

Embedded means that the page, as it opens, calls the document from a remote server — so fast that you can’t see it happen. The page and document pop to your screen from different servers, even from different parts of the world, like a magic rabbit pulled from a hat.

Both page and document display text. That said, you might ask: why not just put all the text in the page and omit the document?

Good question!

The simple reason is that text in documents is easier to edit and manage than text in pages. Moreover lengthy text in documents makes the GMi website lighter, faster, and nimbler as it grows larger and more complex. The design of GMi content is “object-oriented.”

A lighter, faster, nimbler website is great for visitors who know what they’re looking for. They use menus to find data; it comes quickly to their screens.

But menus only list topics that are relatively abstract. Many visitors can’t find what they want using menus, or they can but it takes too long. Instead of menus, they would prefer to use keyword search to find what they need.

There is already a WordPress search bar in the footer of every GMi page for just that reason. Seems reassuring, but it isn’t. Keywords entered there are found in pages, but not in documents.

Why? Because WordPress search reads only words in pages; it can’t read words in documents. You and I can; it can’t.

Up to now, the only way to search documents on GMi has been to open a page and use the search or find option of the browser. That option can read the document displaying on the screen. However it can’t read the documents elsewhere on the website.

If you follow this convoluted explanation, you may see the problem. What’s lacking at present is the ability to perform keyword search on all pages and documents published by GMi: millions of words, instantly, all at the same time, from anywhere on the website.

I didn’t know how to fill that gap. WordPress advisors didn’t know how to do it. Consultants I asked didn’t know how to do it. But ChatGPT figured it out in a few seconds.

The solution (efficient, but still to be implemented and tested) is a Google Programmable Search Engine (PSE).

I must create a PSE that can read Google Drive folders where the documents are saved and published to the web. I add more documents to this Drive almost every day, and that’s okay: the PSE keeps up with changes.

So far so good, but because there is valuable information in pages as well as documents, I must configure the PSE to read pages too. Ergo every word that George Moore wrote and every word that I have written about George gets indexed by the PSE!

When this is done, the last step will be to place a new search bar in the footer of the GMi website, always there for visitors when it’s needed.

That, my friends, is what I call revving the search engine. Not only will it make a literary legacy more accessible and usable, it will also add a quantum leap in interactivity to the simulation of George Moore that is already on the horizon and heading our way.

Call the Midwife?

Nearly a century after George Moore wrote his brilliant autobiographical trilogy, an English nurse named Jennifer Worth wrote one of her own.

George’s was named Hail and Farewell! in three volumes: Ave (1911), Salve (1912), and Vale (1914). You’ll find them all on GMi (plus PDFs to share with your AI study-buddy).

Jennifer’s was named Call the Midwife in three volumes: Call the Midwife (2002), Shadows of the Workhouse (2005) and Farewell to The East End (2009).

Though Jennifer never mentioned George (to my knowledge), her trilogy had much in common with his novel Esther Waters (1894). In their books, both authors were inspired, with indignation and empathy, by “how the other half lives.” Both acknowledged, candidly described and honored the struggles of women in a society that objectified and mostly took women for granted.

And of course, both authors were awestruck by the moral and aesthetic paradigm of mother and child. If she had read Esther Waters, Jennifer would surely have endorsed what George wrote about his protagonist:

Hers is an heroic adventure if one considers it: a mother’s fight for the life of her child against all the forces that civilisation arrays against the lowly and the illegitimate. She is in a situation to-day, but on what security does she hold it? She is strangely dependent on her own health, and still more upon the fortunes and the personal caprice of her employers. Esther realised the perils of her life very acutely; she trembled when an outcast mother at the corner of a street stretched out of her rags a brown hand and arm, asking alms for the sake of the little children. Three months out of a situation, and she too would be on the street as flower-seller, match-seller, or — (Esther Waters, 1894, page 163)

As a flower-seller, yes. but not one like Eliza Doolittle in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (1913). Esther was a creative force, not a man’s creation. “I should ’ave liked quite a different kind of life, but we don’t choose our lives, we just makes the best of them” (page 294).

Unfortunately Esther couldn’t be dolled up by an egomaniacal professor to live happily ever after. In life, as her author understood it, no one ever is.

On Television

Every year since 2012, a series on television based on Jennifer’s memoirs has been broadcast in the UK and the USA. I’m a fan; I have watched it from the beginning and want it to continue forever, God willing.

Just prior to Call the Midwife, its producer Heidi Thomas revived Upstairs, Downstairs, a hugely successful television series of the 1970s. Upstairs, Downstairs is another analog of Esther Waters, likewise set in London just a few years later and focused on the servant class (or caste). You can stream the original and the reboot (I did).

It’s too bad that Heidi didn’t consider Esther as her next project. Maybe there’s still time?

Actual to Plan

I promised last month to transcribe A Modern Lover (1883) for GMi, but printed book scanning at UDelaware is taking a while. Rather than sit around twiddling my thumbs, I shifted to Esther Waters: it is now available on GMi in various formats.

Esther Waters was many things, among them a fresh beginning for its hard-working but frustrated author. The story once again took place in Sussex and London, but gone were several unpleasant characters that George had reprised since his career as a novelist began with A Modern Lover.

Gone too was the short sprint. Esther Waters had 142,000 words in 49 chapters. It was George’s largest project since A Mummer’s Wife (1885) with 174,000 words in 30 chapters.

Esther Waters is far too rich in meaning and drama to be summarized here. In my opinion, it’s a masterpiece and magnum opus. I must only mention the striking minor character of Sarah Tucker, whom I forgot until revisiting the novel and now keep thinking about.

Sarah is a decadent counterpoint to Esther, almost the subject of a different story that George didn’t write. Sarah is perhaps truer to life than Esther is; she may be our dour and pessimistic author’s reminder that hardship and sacrifice don’t necessarily, or even usually, lead to redemption.

After Esther

Esther’s illegitimate son Jackie was mostly raised by Mrs. Lewis, a foster parent who lived at 13 Poplar Road, Dulwich. I mention that here because George’s next big project, a duology he took several years to write, featured a heroine who also called Dulwich home.

As age and solitude overtake us, the realities of life float away and we become more and more sensible to the mystery which surrounds us. And our Lord Jesus Christ gave us love and prayer so that we might see a little further. (Esther Waters, 1894, page 369)

So said the devout Mrs. Barfield to her worldly son. So may Evelyn Innes say in George’s new story about to be written.

Letters Update

George Moore’s letters of 1896 are now live on GMi.

In the afterglow of success and celebrity with Esther Waters (1894) and after taking care of unfinished business with Celibates (1895), in 1896 George pivoted to full-time research and development of his ambitious duology Evelyn Innes (1898) and Sister Teresa (1901).

He was no longer a writer of realistic or psychological fiction (his brand) or a columnist in the London press (his job). Instead he self-consciously became (truly what he always was): a dreamer. He threw himself wholly into spiritual, ethereal and symbolist themes.

His immersion in Wagnerism catalyzed the pivot, and his excitement about the revival of ancient music cemented it. He became more mindful than ever of intangible, invisible, nonverbal powers that spring from and act upon human nature.

He could feel Yeats coming around the corner!

His pivot also offered an escape hatch from fin de siècle decadence and growing feelings of revulsion from materialism (feelings that triggered his repatriation to Ireland at the turn of the century).

On a less lofty level, the pivot satisfied the needs (according to me) of our inveterate contrarian to avoid doing the logical, expected, normal, agreeable, self-aggrandizing thing. Rebel-producer George always enjoyed finding ways to break things and remake them with a difference.

According to me, 1896 was also the year his daughter Nancy Cunard was born. Her birth isn’t mentioned (at all) in the letters. His affair with her mother was a carefully guarded secret, but an acknowledged fact nonetheless. We can only infer what Nancy meant to him from his future devotion to her, and perhaps from the loving testament to parenting he wove into Esther Waters.

Letter to Tolstoy

A gratifying achievement among the letters of 1896 is the inclusion of George Moore’s only letter to Leo Tolstoy.

I learned about it 45 years ago but hadn’t seen it until yesterday when the Leo Tolstoy State Museum (Moscow) sent me photographs. They also sent a revealing letter to George that he was honored to receive and proud to share with the great Russian novelist. Both letters are here.

George’s well-known first love of Balzac was certainly not his last. He was a huge fan of Tolstoy and Turgenev, and Dostoevsky to a degree. The Russian masters provided a roadmap away from French naturalism towards his emerging ideal of symbols and spirit.

Next Up

Having just renewed my acquaintance with the spinster Miss Rice in Esther Waters, I’m now looking forward to meeting her kith in Celibates (1895). I vaguely recall that doleful collection of stories as a throwback or piece of unfinished business, a collection of ideas that escaped the wastebasket.

But was it? Best way to find out is to put it up on GMi, and help my human and machine readers form their own opinions.

I have also got the letters of 1897 on the workbench. I can’t promise anything as surprising as a letter to Tolstoy, but we are not about picking and choosing the tastiest morsels at the banquet. Let’s enjoy it all!

Bob Becker (16 August 2025)