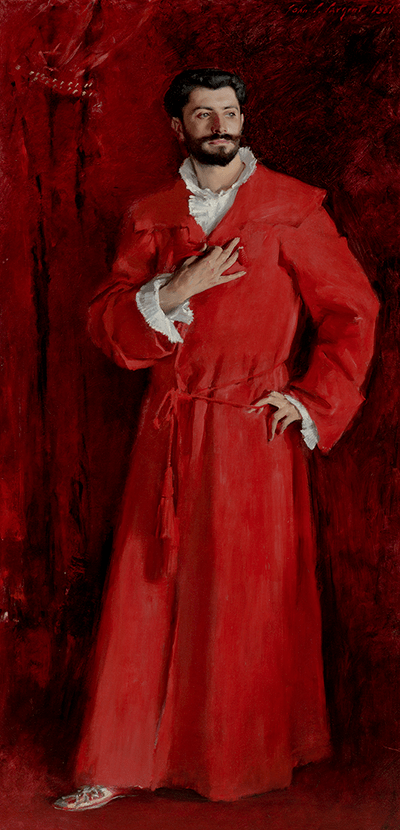

Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881), oil on canvas by John Singer Sargent in the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (Wikimedia Commons). Because ineluctable charisma is part and parcel of Mike Fletcher, I put this picture on the cover or the eponymous novel. Sargent painted the debonair French gynecologist while George Moore was beginning his literary career, sifting through recent life experiences that he would memorialize in Mike Fletcher (1889) and other stories. Like the character Mike, the fashionable doctor was intelligent, sensual, artistic, successful — though not a Don Juan. It’s easy to imagine him sharing a flat in the Temple with Frank Escott, having his full English breakfast after a night of cultivated debauchery, looking just like he did in Sargent’s portrait and just like Mike Fletcher did in George’s wayward imagination.

New Confessions

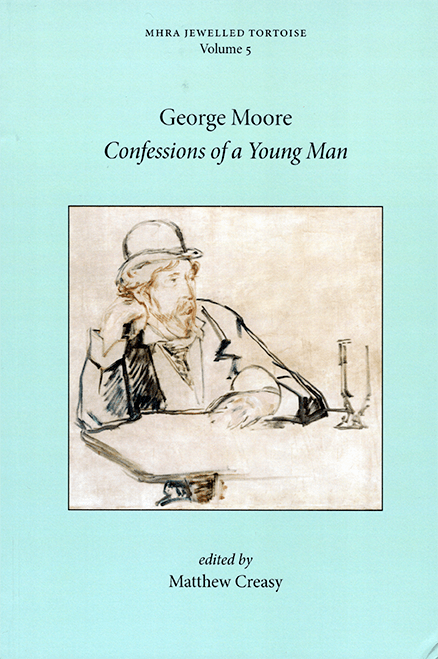

A rare and wonderful thing has appeared: a new edition of a book by George Moore! Not a reprint, not an academic monograph, but the real McCoy (albeit dressed in scholarly finery). Move over Susan Dick!

I’ll add it to the Bibliography of George Moore when I have time to take its measurements. As you know, Edwin Gilcher’s published data are digital on GMi. They’re about to grow.

Nine Projects

Expansion of Edwin’s A Bibliography of George Moore is one of nine projects that Resurgam will be asked to fund. Edwin’s published data stop in 1988, though he kept collecting until he died in 2002. His papers at Arizona State University may yield new bibliographical entries when they’re scrutinized. He told us they would.

Beyond reviewing Edwin’s legacy, though, libraries and the Internet will be searched for George Moore’s books and pamphlets, contributions, periodical publications, and translations that made it into print over the past 25 years. We shall find them! They shall be corralled!

There probably aren’t many unknown publications because the eclipse of George Moore is relentless (despite the efforts of a few nonconformists). That said, whatever GMi finds with the support of Resurgam will merge with the digital Bibliography, so that George’s marvelous literary legacy will be fully up to date, updatable, freely accessible, and poised for long-awaited growth.

And the other eight projects? I’ll write about them in a future newsletter. With a little bit of luck, GMi may soon be hiring.

Boys Club

I’ve said that George Moore’s fiction between A Mummer’s Wife (1885) and Esther Waters (1894) is like a walk through the valley of the shadow of death. Then, each time I reread one of the dark volumes, I change my mind. They are flawed but not bad. They are conflicted but not defeated.

Mike Fletcher (1889) is the latest title to change my mind. The edited digital text is now available, chapter by chapter, on GMi; a free ebook is in the GMi Shop. Assuming that you already have more books than time to read, I should try to explain why Mike Fletcher may be worthy of consideration.

I offer two arguments. One is aesthetic in the spirit of art for art’s sake. Read Mike Fletcher because it burns with a gemlike flame! The writing is good, the theme is meaningful, the characters are interesting, the local color shimmers. My second argument is parochial. Read Mike Fletcher to deepen your slim understanding of the man who wrote it.

Parochial

Turning first to the parochial, I remind you that Mike Fletcher (1889) was written around the same time as Confessions of a Young Man (1888). The first book is a memoir, the second is a novel, but both were written by a young man who was keenly, avidly self-aware (ergo full of himself).

So it shouldn’t surprise us that Mike Fletcher is borderline memoir, just as Confessions of a Young Man is borderline fiction.

Want to know what life was like in London’s Temple in the 1880s, when George lived there? Mike Fletcher informs us about that, in detail. Mike and George lived in the same building, maybe even the same flat.

Want to know what life was like for Irish journalists in Fleet Street when George was one of them? Mike Fletcher informs us about that too. The novel is fondly dedicated to Augustus Moore, George’s lascivious brother and collaborator who modeled the characters of Mike Fletcher and Frank Escott (both Irish). Escott’s Pilgrim was an analog of the Bat and the Hawk, real weekly newspapers that Augustus edited and George contributed to.

I haven’t studied the text of Mike Fletcher in order to write a monograph (you’re welcome), but I’m pretty sure that a good one could be written, defending my hypothesis that Mike Fletcher is as autobiographical as Confessions. “Only the names have been changed to protect the innocent.”

George as a self-taught, self-directed writer was a shapeshifter — crossing the frontiers of literary genres without a guide, experimenting with different styles of self-expression. In a creative quest to tell his truth, he did not mind if the subject matter was real or pretend. The invented Mike Fletcher has a lot to say about the historic George Moore.

Aesthetic

The other reason to read Mike Fletcher is for enjoyment. Candidly, I’m not sure how enjoyable the novel is! The experience of line-editing is not compatible with losing oneself in a story. Yet I think Mike Fletcher can be read in 2025 for its own sake.

In addition to introducing the Pozzi-like main character, the novel reprises Frank Escott from Spring Days (1888), John Norton from A Mere Accident (1887), John Harding and Alice Barton from A Drama in Muslin (1886), Dick Lennox from A Mummer’s Wife (1885), and Lewis Seymour from A Modern Lover (1883). George may have been brewing a mini Human Comedy in the 1880s, so it’s worth keeping up with his people.

I refer to Mike Fletcher as a Boys Club because George wrote it as the obverse of A Drama in Muslin. He told the story, as he saw it, of wasted young female lives in the earlier novel; now he would tell the story of wasted young male lives “of my generation.” How utterly sad!

Maybe more important than plot or character, Mike Fletcher dwells on — dare I say it? — the “timeless theme” of Don Juan. I hesitate because George’s erstwhile publisher William Swan Sonnenschein told him, when rejecting George’s submission, that the very idea of reimagining Don Juan in 1888 was preposterous and uncommercial. (George Bernard Shaw wasn’t copied on that letter). George took his project to Ward and Downey, an offshoot of William Tinsley, the publisher of A Modern Lover.

As if to cozy up to readers in the twenty-first century, Mike Fletcher began with the sexual assault of a young woman. The Me-Too movement did not turn up in a lot of Victorian fiction, but it did here. True to life if not wishful thinking, Mike was not remorseful. His lusty bravado continued throughout the novel, even reverting to his first victim as she lay dying of tuberculosis. Mike was attractive and disgusting, yes, and that was partly George’s point.

You have to wait until the end of the novel for the point to be made, not just in horrid actions but in pessimistic philosophy:

His life had been from the first a series of attempts to escape from the idea. His loves, his poetry, his restlessness were all derivative from this one idea. Among those whose brain plays a part in their existence there is a life idea, and this idea governs them and leads them to a certain and predestined end; and all struggles with it are delusions. A life idea in the higher classes of mind, a life instinct in the lower. It were almost idle to differentiate between them, both may be included under the generic title of the soul, and the drama involved in such conflict is always of the highest interest, for if we do not read the story of our own soul, we read in each the story of a soul that might have been ours, and that passed very near to us; and who reading of Mike’s torment is fortunate enough to say, “I know nothing of what is written there.” Mike Fletcher, Chapter 11, page 295.

Mike is a kind of Meursault, fifty years before that existential anomaly strolled along an Algerian beach. He is a carrier of “life force” before George Bernard Shaw dressed it in a positivist cape. He is the masculine ideal that dominates the entertainment arts today: intelligent, sensual, artistic, successful — and brutal once lofty sentiments are swept aside. “I alone am alone! The whole world is in love with me, and I’m utterly alone” (page 263).

I suppose it isn’t a spoiler to reveal that Mike takes his own life rather than conform in a world that idolizes him. I have to tell it because that detail is vital to the novel’s relevance today. Suicides are increasing at alarming rates, while civilization is bent on mass extinction. We are strangely, incoherently self-destructive.

George Moore recognized something like that in the 1880s and chose to do the unpopular thing: write a book (actually a series of books) exposing it. Not very uplifting, I grant that, but still very cool.

Letters Update

The letters of George Moore on GMi are now complete through 1894. What about that year stands out in his legacy?

The publication of Esther Waters on 1 March 1894 was a milestone in his career. Before that he was, to put it mildly, in a pickle. It’s fair to say that he had touched bottom and seemed unable to rise again.

On the personal side, his Irish estate was producing no income because of political turmoil. Moreover his mother’s siblings were threatening financial ruin by demanding payment of a large debt forgotten for twenty years past.

On the professional side, all seven of his novels had been ranked indecent and banned by the country’s leading booksellers (his eighth would also be banned).

His stalwart publisher Henry Vizetelly had died after being prosecuted, driven into bankruptcy, and imprisoned for publishing books that George had recommended and helped produce. Other publishers who then stepped up for George didn’t stay long.

His only critical and commercial success in fiction was nearly ten years old. The novels he published before and after A Mummer’s Wife were pretentious, moody, unpleasant for the most part though well written, and sold poorly.

As he finished writing Esther Waters for the Newcastle publisher Walter Scott, his submission of the manuscript was declined by America’s three leading publishers and accepted by none, resulting in his loss of American copyright.

As a novelist, George was not making a lot a money and not receiving much respect or encouragement from critics or readers. He was about to come out with the untoward story of a promiscuous servant girl who gets impregnated by a boyfriend who then abandons her. It is the life story of an uneducated, nearly unemployable, distressed single mother with no prospects.

What could go wrong?

What amazes me about George at this time, and really at all times, is his resilience. Facing very strong headwinds, he did not complain, did not adapt to the market, did not change his profession. did not shut up, did not stop working as hard as he could for his “life idea.”

He behaved like a character in Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable, as he responded to massive adversity with something like: “Where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

And then suddenly, practically overnight, against all odds, he was the author of a masterpiece.

Editorial Principle

I’ll take a moment to reiterate an editorial principle concerning the letters, and really everything GMi publishes.

The letters on GMi are digital. Unlike print, they are not typeset, not pressed with ink on to paper. The letters are interactive.

When readers of the letters know something that I don’t know, they can share it right there on the web page, alongside the transcribed letter, with me and our community of interest.

If they own a morbid fascination with George’s bad spelling and punctuation, they can link to the manuscript owner for access to the source material. I correct errors in my transcriptions to make them readable and coherent.

Most importantly, if we learn about letters that are missing from GMi, we can add them the moment they come to light. No waiting for a second edition to come out. No detours to a journal or supplement.

The digital letters of George Moore are a living edition that will grow and improve over time if our community shares what it knows.

I love publishing like this, and pricing the publication of a literary legacy as it should be priced for the benefit of all: free.

Next Up

I feel pretty sure that I haven’t convinced anybody to read Mike Fletcher. Thank God for machine learners who can do the heavy lifting for humans!

Next month, I will add Vain Fortune to the Worlds pillar and the GMi Shop. I don’t know if it’s a happier story; I can’t remember. The title doesn’t augur well. We’ll soon find out.

Next month I will also put the letters of 1895 on the workbench. The character John Norton returns yet again in 1895, like an itch George couldn’t stop scratching. Evelyn Innes will start an itch of her own, emerging from the moody depths of George’s now celebrated soul.