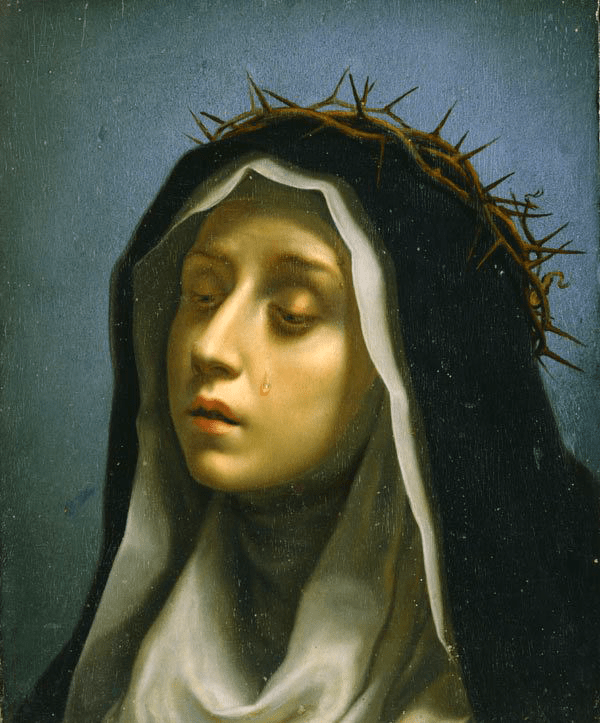

Saint Catherine of Siena (1665–1670), oil on panel by Carlo Dolci in the Dulwich Picture Gallery. George Moore visited the Gallery while planning his duology Evelyn Innes and Sister Teresa; he also situated parts of the story there.

✱

In my October 2025 newsletter I featured Gerrit Dou’s A Woman Playing a Clavichord (1665) from the same Gallery. That painting strongly evokes the character of Evelyn Innes while Saint Catherine of Siena suggests her evolution into Sister Teresa. While it doesn’t purport to depict Teresa of Ávila, the curators have captioned it thus: “Saint Catherine wears a crown of thorns, which refers to a religious vision she had when she was 28. In the vision Christ appeared to Catherine, asking her to choose between a golden crown, ensuring riches in her earthly life, or the crown of thorns, guaranteeing her glory in heaven. Catherine chose the latter.” A more apt description of George’s heroine would be difficult to imagine!

✱

Apart from the religious theme of Dolci’s painting, George would have noticed how adorable the model looks with a tear glistening on her soft cheek and crown of thorns. A soulful woman like this was the ruling passion of Owen Asher’s life.

For Our Time

I’ve written hundreds of times that George Moore is fondly remembered as a purist who made art for art’s sake, and I believe that’s true. Nonetheless I feel proud of him when he occasionally stakes out his moral universe.

For example consider a quote from his Preface to the second English edition of Esther Waters (1899):

It was very generally assumed that [the novel’s] object was to agitate for a law to prevent betting, rather than to exhibit the beauty of the simple heart and so inculcate a love of goodness. The teaching of Esther Waters is as non-combative as that of the Beatitudes. Betting may be an evil, but what is evil is always uncertain, whereas there can be no question that to refrain from judging others, from despising the poor in spirit and those who do not possess the wealth of this world, is certain virtue. That all things that live are to be pitied is the lesson that I learn from reading my book, and that others may learn as much is my hope. [italics added]

The italicized words remind me how a once shining city on a hill tumbled into a vulgar and uncouth gorge of indifference. America today, jingoistic Britain and anti-Drefusard France in the 1890s! George didn’t beat the drum for hope or compassion but somehow inspired them with sorrow and pity.

In a saucier mood a year later, he wrote a Preface to The Bending of the Bough (1900) that also strikes a resonant chord:

Immorality is never persecuted — the world cannot persecute itself; nothing is persecuted in this world except the intelligence.

I’ve noticed this in my life, more keenly since the 2025 assault on science and higher education in America, but rarely heard it uttered plainly. People act today as if cruelty, ignorance, greed, hypocrisy and dishonesty are trivia or collateral damage, not important enough to stop the carousel.

To my knowledge George Moore never saw evil as trivial. At the turn of the century as he neared his 50th year, he stopped the carousel and got off. We’ll soon follow where he went next.

Letters of 1899

In January I transcribed, edited, annotated and published George Moore’s letters of 1899; they’re live now on GMi.

George published no new books and few articles that year; nor did he work much on the sequel to Evelyn Innes. He seems relatively inactive, but his memoirs in Hail and Farewell! Ave show that he wasn’t.

There aren’t enough extant letters to follow him day by day in 1899, but the 40 we have (so far) show that his passion was innovative theater: the established Bayreuther Festspiele and emerging Irish Literary Theatre.

The styles of Richard Wagner and Henrik Ibsen may seem like opposing influences, but to George they were lighthouses guiding the modern arts to a safer harbor.

After editing his letters of 1899 to W. B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, I had to reread The Bending of the Bough to understand what he was talking about! Since my understanding is not more important than yours, I also transcribed, edited and published the play (including a PDF for AI analysis and a link to Edward Martyn’s The Tale of a Town).

Now everybody is on the same page!

This activity prompted a stimulating session with ChatGPT. Unsure what to make of George’s play because it’s so different from what I expected, I asked the chatbot to explain. It gave an interpretation that didn’t jive for me, so we “took it outside” for debate. Heuristics can be fun with artificial intelligence!

Purpose

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

That was according to John Keats in Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819) 80 years before George Moore tested the boundaries in what I choose to call his pivot.

Until the turn of the century George was an aesthete: a notable and highly enjoyable literary ripple sprung in the 1870s, mainly by writings of Théophile Gautier in France and Walter Pater in England. He was a self-described exile from the Nouvelle Athènes who had little use for family, morality, politics, commerce or public affairs except as a framework for storytelling.

For a variety of reasons possibly including midlife crisis, that began to change in the mid 1890s. After the success of Esther Waters, at the end of his tenure as an art critic, arguing for theater reform, on the cusp of his passion for ancient and modern music, he had reached his mid-40s single, a new but unacknowledged father, comfortable, at the top of his professional and social game, but unhappy.

Why so unhappy?

I almost hear him explaining why in the voice of his epitomic heroine: “I have given you all a great deal of trouble. I have never known myself; it is so difficult. I envy those who do; their lot is happier than mine.”

George was unhappy in the way that some depressed people are: his convictions and ambitions for the past quarter century were wobbling. His geyser-like creativity was either waning or looking for a new outlet — who could say for sure at the time?

I believe he met this crisis by self-actualizing. The duology was his way of insisting “I’m not done, but I’m once again going to be different.”

His theme for Evelyn Innes was the trigger: a conflict between art and religion which religion surprisingly wins. For Evelyn and I suppose for her creator, truth wasn’t beauty as previously assumed: they were different and unequal!

In Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) Walter Pater posited that “art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake.”

This worked for George Moore on many levels — in poetry, fiction, memoir, essay and drama — but in general it works better for a younger man. An older man has different yearnings.

I haven’t figured out his yearning but suspect it was for consequence. Like Evelyn Innes in her professed state as Sister Teresa, George wanted proof that life really matters: his own life and those around him. He wanted the carousel to stop so he could get off and commit himself to something new and revitalizing; something that involved his soul along with his senses.

He was not tempted by popularity. One of my favorite quotes surfaced in a letter to the Daily Chronicle (20 January 1899) rebutting the drama critic William Archer: “Mr. Archer must know that the public was, is, and always will be, a filthy cur, feeding upon offal, which the duty of every artist is to kick in the ribs every time the brute crosses his path.”

Those were not the words of man aiming to increase his sales or reputation. They came from one who was tired of bullshit and ready for change. When he wrote them he was waxing under the influence of W. B. Yeats.

George did not follow Evelyn into godliness. He followed Yeats though not into folklore and myth; rather into engagement. He pivoted from an aesthete into a man of action for whom art should have consequences.

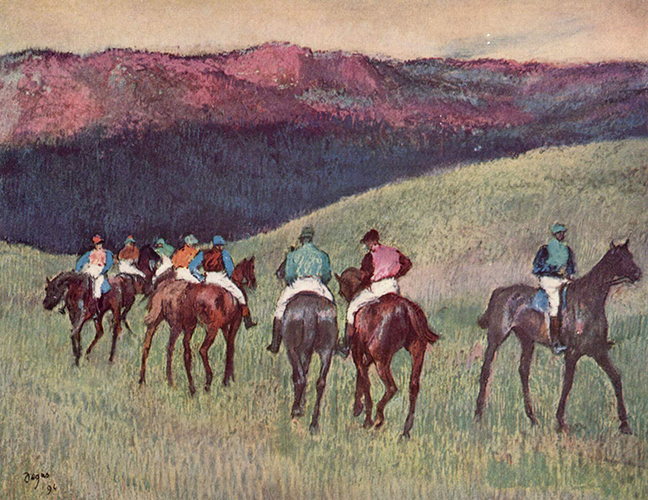

Poplars (wind effect)

One of the most enjoyable tasks I perform for George Moore Interactive is selecting cover art for ebooks. I look for historic images that meet one of more of these criteria:

- Beautiful — for judging an ebook by its cover

- Illustrative — of the ebook’s content

- Consistent — with the author’s discriminating taste

- Contemporary — with his writing of the first edition

- Free — to publish on GMi

Recent selections for Evelyn Innes (1898) and Sister Teresa (1901) were gratifying. I chose paintings that George Moore himself must have seen and pondered in the Dulwich Gallery as he planned his duology.

They picture a female figure in two diametrical modes of being and probably enhance a reader’s understanding or at least appreciation of authorial intent.

More recently I selected cover art for The Bending of the Bough (1900). Textual ambiguity at first made the search difficult: is the play a political allegory (as many seem to think) or a psychological drama in the manner of Henrik Ibsen?

Fresh from my line edit, I decided that The Bending of the Bough is mainly psychological. Its cover should illustrate the proverb implicit in the book title: The wind does not break a tree that bends.

That decision freed me to illustrate a metaphor of the human condition rather than an allegory of Irish nationalism before independence. It put my quest on a level much more germane to George’s sensibility.

My choice was a painting by George’s friend Claude Monet. The contrast between vertical trees in the foreground, seemingly unfazed by the wind, and the distant windswept trees reflects a contrast in the play between the towns of Southhaven and Northhaven, and on another level between the two main characters Ralf Kirwan and Jasper Dean.

Monet finished his painting eight years before George wrote his play. I don’t know if George ever saw it but feel sure that he loved it if he did.

Next Up

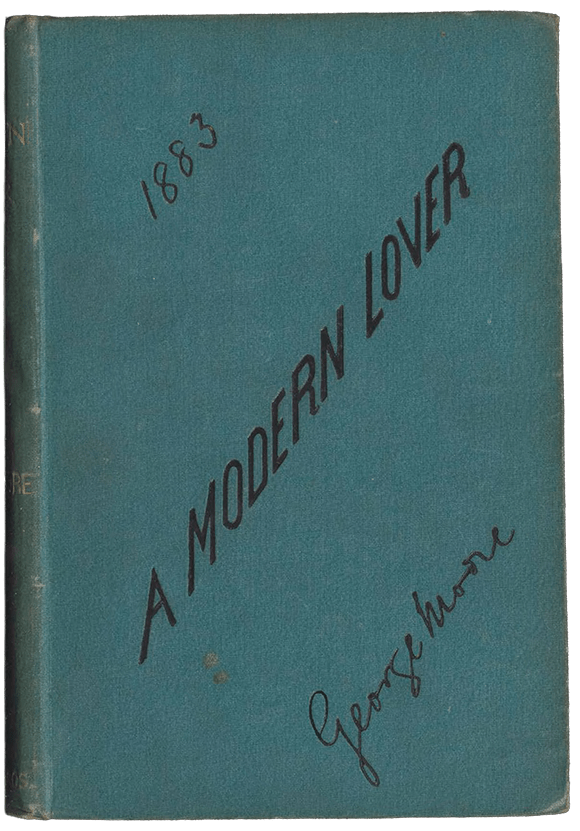

Thanks to the generosity of Mr. Mark Samuels Lasner and the MARK SAMUELS LASNER Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press, the world now has a clean digital scan of the first edition of A Modern Lover (1883).

This was George Moore’s first novel, the hardest to find in libraries and booksellers and nowhere to be found in digital archives. It was a cornerstone of George’s fiction in the 1880s and 1890s, up until his pivot at the turn of the century.

At my request, Mark had his copy of this rarest of rare books scanned; as an in-kind donation to George Moore Interactive, he provided a PDF that I will transcribe and publish in February.

I may be the only person in the world that is excited about this; if that is true, so be it! A seminal text that cannot be overlooked with impunity will no longer be overlooked. Thank you, Mark!

In addition to A Modern Lover, I will transcribe, edit, annotate and publish the letters George Moore wrote in 1900.

His letters through 1899 are already live on GMi; we are now approaching the halfway point in his career and his consequential move to Ireland in 1901.

I will try to get through all of this in February, but I can’t promise because the Resurgam doorbell is ringing again and I must go answer. We have obtained a fresh list of foundations that seem qualified to kickstart literary legacies in the digital age. I will study the new list and sort for the best prospects.

Grant applications for Resurgam projects are likely to follow soon.

Reminder!

George’s 174th birthday will be on 24 February 2026. If you’re near Moore Hall that day and the weather is decent, rent a boat and visit his grave on Castle Island. And give him my love if you see him.

Bob Becker, 22 January 2026

Show your support. Please subscribe.