I recently hung a lot more pictures in the digital galleries of George Moore Interactive. The Iconography has grown.

If you follow this project, you already know that most of the extant portraits of George Moore have been roped in. A major one still eluding discovery, in some private collection in the United States, is a portrait by John Singer Sargent. Existence, not in doubt; current whereabouts, unknown.

A different major one, a picture that Bruce Arnold rated as William Orpen’s “masterpiece,” the whereabouts of which were previously unknown, has now suddenly come to light. Eureka! and moreover to colorful light, because my colleague Michael O’Shea went to London to view and make a color snap of it.

Having found that elusive masterpiece — a picture that Moore himself commissioned and owned for thirty years — I am frustrated because though I know where it hangs, I can’t tell you. The owner wants to remain anonymous. But I hope that a museum in Ireland will one day buy it, clean it thoroughly, and hang it in a public gallery where everybody can enjoy it.

Pictures of George Moore are all very well, but the Iconography has grown still larger. It now includes portraits — many of them self-portraits — of artists who knew George as a friend and painted, sketched or photographed him. Moreover each portrait of the artist dates from the time of his or her contact with George Moore. My goal was to show the artist that Moore was watching while the artist was painting him. Reciprocal images? Mission accomplished.

An artist picturing George Moore is analogous to a publisher bringing out his texts. Scholars often look beyond publishers as though they were not central to building literary legacies, when in fact there would be no such legacies without the direct, collaborative, often crucial involvement of publishers.

For this reason, I have brought George’s publishers in from the cold. I have curated a gallery of publishers who worked closely with him — from William Tinsley all the way to William Heinemann. You will now find them in the Iconography, sometimes accompanied by book designs they fostered.

I have not included publishers that never met George Moore, since they didn’t actually work alongside him, but some curious impulse urges me to add Rupert Hart-Davis and Colin Smythe, both of whom deserve a place in this pantheon. If there were more publishers like Rupert and Colin today, enduring literary legacies would be found in many more bookstores and libraries.

With artists and publishers now hanging in GMi galleries, I could hardly ignore George’s family members. After all, some were generators of his DNA, others were stakeholders in his legacy.

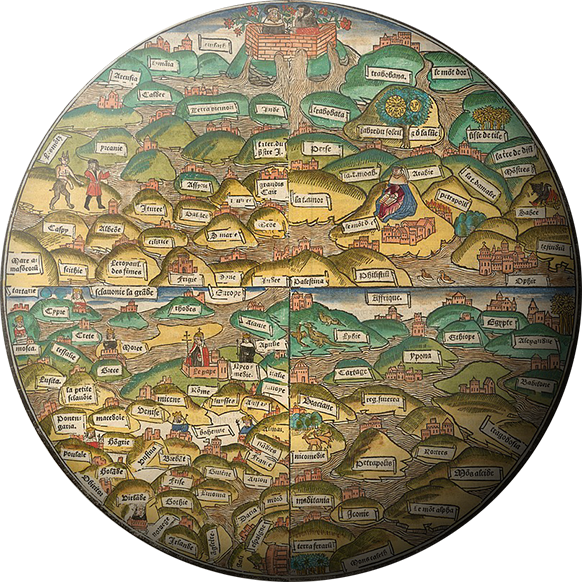

That said, you can now find a Moore family tree in the Iconography, going backwards and forwards from grands and parents to siblings and their offspring. I included Nancy Cunard in the tree, though Nancy herself was known to disagree. I think George would approve.

While still more people are lining up for inclusion in the Iconography, my attention has been diverted from them to places where George Moore lived and visited. It may be wondered what value and meaning attaches to a place where a great writer was situated at various moments in his life. I am not prepared to explain it, but I feel sure that place matters to the writer, to the writing, and to readers like me who want to grasp the real world lurking behind the author’s worldbuilding.

The Places gallery of the Iconography now shows all the homes and other buildings where Moore literally wrote things: all the return addresses in his letters. Most of the images are vintage; the rest depict buildings whose appearance has changed little since Moore was there. Just ignore the cars parked on the curb.

With the Places gallery, it is now a bit easier to see the world surrounding the author as he himself saw it; and it will become easier still when I add more places. My initial foray was to capture the places where Moore wrote; next is to capture places he is known to have frequented but didn’t write from.

The first of this kind are homes of Lady Cunard after she left Nevill Holt. Her homes were never George’s return address, and her biographers and Moore’s have mostly ignored them, but we may feel certain that he was a frequent visitor, and his time in those houses was extremely important to him.

Textract

“Amazon Textract goes beyond simple optical character recognition (OCR) by extracting relationships and structures between elements from documents.”

That quite remarkable claim is made almost in passing by Amazon Web Services about a business application GMi will use to “kickstart literary legacies in the digital age.”

The claim is remarkable because it captures what may be the essence of textual scholarship and literary criticism as practiced in the academy; but in this case it is practiced by machines in the cloud, to levels of accuracy and integration undreamed of in old schools.

“When extracting information from documents, Amazon Textract returns a confidence score for everything it identifies so that you can make informed decisions about how to use the results. For example, if you … want to ensure high accuracy, you can flag any item with a confidence score below 95 percent to be reviewed by a human.”

Is your jaw beginning to drop? If not, maybe you should read that quote again. It bolsters the first claim by saying that machines performing textual analysis (and literary criticism) perform a task that is traditionally delegated to the slowest and most prejudiced humans in our world: peer reviewers.

Artificially intelligent machines tell us, the human consumers of their labor, how trustworthy their work is (according to numerous objective measures derived from machine learning on a vast scale). The machines tell us, in effect, “these are the things I feel very confident about, you can depend on them; these other things are probably okay but you should investigate to make sure of them.”

“…many text-extraction use cases and applications require humans to review low-confidence predictions to ensure that the results are correct. But building custom human reviewing systems is time consuming and expensive. Amazon Textract is directly integrated with Amazon A2I for you to implement human-review extracted text with low confidence scores from documents. You can choose from a pool of reviewers within your organization, or access the workforce of over 500,000 independent contractors who are already performing ML tasks through Amazon Mechanical Turk.”

I do not expect anybody reading this blog to appreciate the disruption in that statement, but it is epic. It signals that slow and labor intensive work of assuring the quality of a literacy legacy can be speeded up: first by making the process of troubleshooting significantly faster and more efficient, and second by ironing out the digital wrinkles with a host of inexpensive, on-call human helpers.

Some might say, “why would I assign that work to low-cost skilled helpers when I can get it done for free by unskilled students?” The answer may be that the academic-industrial process in the humanities is not going to last forever; some believe that it has already collapsed; and therefore new ways of doing important work at scale are needed.

Evelyn Innes and Sister Teresa

Until recently, if you asked me which of George Moore’s novels are least susceptible to kickstarting in the digital age, I would have answered Evelyn Innes (1898) and Sister Teresa (1901). They are just so… dated?

That was before I encountered Catherine Coldstream, the author of Cloistered: My Years as a Nun (2024). I am not saying that Catherine embodies Evelyn, but rather that she seems to channel much of what George Moore was concerned about when he conceived his symbolist duology.

This resonance of Moore’s legacy with contemporary dilemmas has always struck me as the most overlooked quality of his canon, in an age that prefers to deconstruct recondite authors in (usually vain) hopes of finding something interesting to talk about. Catherine Coldstream has made me feel that even the most recalcitrant of Moore’s novels is poised for a fresh start.