Candid Programs

Resurgam NFP is the grantseeking and grantmaking organization that kickstarts literary legacies in the digital age. If you wish to donate to George Moore Interactive, please send your money to Resurgam and earmark it for GMi.

This deft two-step will ensure that 100% of your donation gets used according to your wishes. Your donation will be objectively managed and accounted for, and the tangible results of your generosity will be reported back to you with thanks.

The two-step will also ensure that your donation is tax-deductible (if you’re located in the United States), which would not be the case if you donated directly to GMi. Here’s a Resurgam page that explains how it works.

Resurgam is an independent, 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation that echoes and reinforces the aims of George Moore Interactive but with a difference. The difference is this: GMi is kickstarting one particular literary legacy, whereas Resurgam wants to animate every legacy — literary, artistic, musical — bequeathed to our world by creative geniuses of the past.

The technology for kickstarting literary legacies has already been invented; it is known by the rubric generative artificial intelligence and is doing amazing things, though not the things that GMi is pioneering. Visit Resurgam’s Comparisons page for more about that.

With useful technology that is now available and the reliable promise of more powerful tools to come in the next few years, all that remains for George Moore to live again is to put our human feet on the kickstarter and push down forcefully.

My foot has been pushing forcefully for George Moore. Now with around 1,700 pages and posts on this website, and more appearing day by day, I can feel the rumble though the handlebars in my grip. I’m thrilled and ready to take the next steps.

But readiness begs the question: what are the next steps? How far into the future can I see when claiming that I’m poised to accept your donation? To be honest, not very far.

I founded GMi with a concept rather than a program; a vision rather than a plan. I wanted to make stuff like a builder rather than talk about stuff like a professor. That action-orientation allowed me to leapfrog important questions such as: What is my program? What is my step-by-step? What are my milestones and endgame?

The recent formation of Resurgam has forced me to step back and consider. Before now, I was happy just to crank out content, with a methodology and a sense of direction, but without a program per se. That has changed.

It changed because, after starting a Gofundme campaign that fell short of my goals, I’m now planning to ask Resurgam for financial support, and I can’t do that without a program; in other words, without short and long term plans.

I realized this as I prepared Resurgam’s bona fides as a legal not-for-profit. Part of that involved joining Forefront, and as a result of joining Forefront I joined Candid. Candid is the organization that runs the Foundation Directory and Guidestar.

To cement my membership in Candid, I needed to state Resurgam’s own program. I did that by pondering the (nonexistent) program of GMi as I had never done before.

The result is not one but four linear Resurgam programs, each of which represents fundable activities that are sanctioned by Resurgam’s mission and for which Resurgam accepts donations.

Resurgam may evolve into other programs as well, but these four are a complete statement of the work being done and planned by GMi.

Consider:

Program 1: Digital Curation

Digital Curation (DC) locates, organizes, scans, transcribes, edits, annotates, illustrates, and preserves the meaningful and influential contents of aesthetic legacies. Legacies prioritized by Resurgam are literary, artistic and musical from antiquity to the twentieth century. DC is foundational to more advanced programs supported by Resurgam.

Program 2: Access to Cultural Heritage

Access to Cultural Heritage (ACH) follows our DC program. ACH publishes and otherwise disseminates the contents of curated legacies in machine- and human-readable digital formats. ACH is limited to formats that are free and easy to use by the general public and compatible with the training of large language models owned by corporations. ACH permits few (if any) technical, financial, and geographic barriers to entry to a curated legacy.

Program 3: Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence (MLAI) follows our DC and ACH programs. MLAI engineers curated and published legacies to ensure they are open to computerized and human-prompted textual, visual and quantitative analysis. MLAI optimizes digital legacies for self-assembly, self-correction, self-validation, date-stamping, cross-referencing, interpretation, elucidation, and correlation with the critical heritage. MLAI synchronizes different digital legacies that have overlapping content.

Program 4: High-Fidelity Simulation

High-Fidelity Simulation (HFS) follows our DC, ACH, and MLAI programs. HFS enables curated, published, and engineered legacies to speak for themselves (by demonstrating autonomous self-awareness and dynamic self-expression). HFS manifests in interactive, lifelike conversations between aesthetic legacies and human interlocutors. HFS may be achieved in digital modalities including chatbot, natural-language processing, speech synthesis, virtual- and augmented-realities, and computer-generated imagery (CGI).

✱ ✱ ✱

Up to the present, everything GMi has achieved aligns with Resurgam Programs 1 and 2, though a lot more remains to be done in those programs. Programs 3 and 4 are still prospective, but here they are defined whereas before they were dreamlike.

When I submit my grant applications to Resurgam, and when you tender your donation, we will have to be clear about program fit. No longer happy to crank out content for its own sake, the work that may be deemed worthy of funding must explicitly advance a program objective.

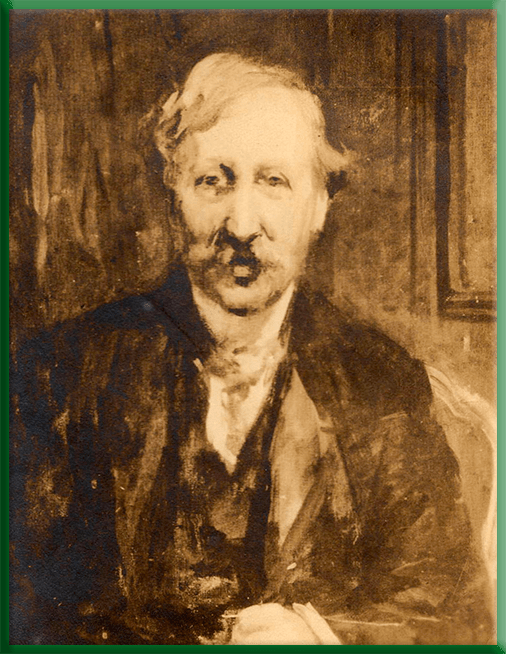

The Worst Novel?

Last month I corrected my mistake in calling George Moore’s A Mere Accident (1887) the worst novel ever written. That dubious distinction purportedly belonged to Spring Days (1888). Worst according to a literary critic whom George respected; worst according to the bewildered author himself.

I promised to transcribe, edit and publish Spring Days, my way of exhuming the victim of literary malfeasance and performing forensic analysis. I have performed it, and now so can you.

The first edition of Spring Days is available on GMi; soon the ebook will arrive in the GMi Shop. All for free. You have what you need to judge for yourself.

My personal opinion of Spring Days is not rancorous. To me, it isn’t a terrible novel; it’s not even a bad novel. As usual when surveying this part of George’s legacy, I’m calling it an experimental novel.

Our ambitious author had a modernist axe to grind, a serious thematic purpose, a good dramatic idea, characters that live on and between the lines, and a richly colored mise en scène.

That said, it is also true that the novel didn’t cross the finish line as a memorable achievement. Not then, not now.

One problem is the title, which sucks (as usual). If you read the book you may wonder, on page after page, why is it named Spring Days? That vague, not catchy title has nothing to do with the plot! The actual words “Spring Days” turn up once, at the very end of the last chapter, almost like an afterthought or the relic of a different novel that was never written.

Another problem is inconsistency. Chapters range in length from 1,000 to 22,000 words. Granted there is no rule that chapters of a novel must be similar in length, but the disparities here look like flaws of construction, reminding me of the Buster Keaton movie One Week (1920) except the movie is funny and this novel isn’t.

A more serious problem with Spring Days is the changing subject matter. At first the story is about the Brookes family: the widower James, his young adult daughters Grace, Maggie and Sally, and his son Willy. The three sisters are foregrounded, like Alice and Olive Barton in A Drama in Muslin.

But no, the narrative soon drifts away from the girls in favor of their pathetic though genuine brother Willy, at first a minor character who unexpectedly grows into a significant moral presence. But that too doesn’t last.

Willy’s friend Frank Escott, at first little more than a colorful detail in the background, suddenly becomes the novel’s main protagonist.

Each of these human loci would be fine as the subject of his or her own story, but the succession of stories, without much in the way of segues, tested this reader’s enjoyment of Spring Days.

If Frank Escott truly is the unrivaled protagonist of Spring Days, that would make sense because he walks and talks like an author surrogate, somewhat like John Norton in A Mere Accident and John Harding in A Drama in Muslin.

Don’t get me wrong, these three men have as many differences as similarities, but a case can be made that George Moore performed in these novels as a ventriloquist whose speech and perceptions were at least partially embodied in Escott, Norton and Harding.

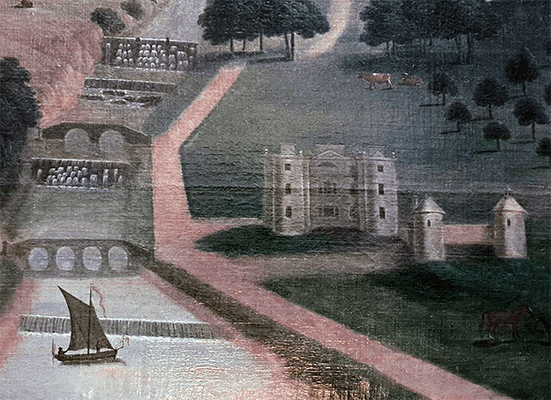

Of course it isn’t necessary for an experimental novel to have a main protagonist because, in my opinion, this novel’s raison d’être is a fictional rendering of the author’s real-life friends the Bridger family and their homes near Shoreham-by-Sea in Sussex.

That helps explain Frank’s rented home in nearby Southwick, where George Moore actually lived while writing Spring Days. From this point of view, it is easier to explain the purported differences between Celt and Saxon, that bubbled to the surface of the novel from time to time.

Frank and George living in Southwick were Irish, the Brookes and the Bridgers living in Shoreham were English. Exploring the evident ethnic differences between these tribes is probably what made Spring Days a worthy project for a renegade disciple of Émile Zola.

(Coincidentally while preparing Spring Days for GMi, I acquired cartes de visite of Harry Colvill Bridger and his daughters Florence and Dulcibella. They are published on the Bridger pages of the GMi Iconography. Use the search bar to find them.)

As mentioned earlier, apart from biographical and sociological interests, Spring Days exhibits a serious novelistic purpose. The purpose is intimated in the following quote, one of several in the book that wax philosophical:

A man’s struggles in the web of a vile love are as pitiful as those of a fly in the meshes of the spider; he crawls to the edge, but only to ensnare himself more completely; he takes pleasure in ridiculing her, but whether he praises or blames, she remains mistress of his life; all threads are equally fatal, and each that should have served to bear him out of the trap only goes to bind him faster. A man in love suggests the spider’s web, and when he is seeking to escape from a woman that will degrade his life, the cruelty which is added completes and perfects the comparison. A man’s love for a common woman is as a fire in his vitals; sometimes it seems quenched, sometimes it is torn out by angry hands, but always some spark remains; it contrives to unite about its victim, and in the end has its way. It is a cancerous disease, but it cannot be cut out like a cancer. It is more deadly; it is inexplicable. All good things, wealth and honour, are forfeited for it; long years of toil, trouble, privation of all kinds are willingly accepted; on one side all the sweetness of the world, on the other nothing of worth, often vice, meanness, ill temper, all that go to make life a madness and a terror; twenty, thirty, forty, perhaps fifty years lie ahead of him and her, but the years and their burdens are not for his eyes any more than the flowers he elects to disdain. Love is blind, but sometimes there is no love. How then shall we explain this inexplicable mystery; wonderful riddle that none shall explain and that every generation propounds?

Spring Days (1888), pages 361- 362.

By this point in the novel (the end), Frank Escott the amateur painter was becoming a novelist, exactly the life trajectory of his creator.

His mind was absorbed in a novel, which he narrated when Willy came to see him. It concerned the accident that led a man not to marry the woman he loved, and was in the main an incoherent version of his own life at Southwick.

Spring Days (1888), page 363

You’ll find a photo of George Moore’s home in Southwick on GMi. He and his fictional Frank Escott were symbolic roommates there; he and his fictional Willy Brookes (modeled by Harry Colvill Bridger) were literal roommates in Freshcombe Lodge.

Letters of 1893

The letters of George Moore, published on GMi, are now complete through the year 1893. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of George’s life in 1893 was his hard, experimental work on Esther Waters (1894). This time, the experiment ended in success!

I cannot begin to fathom how George rose, in just a few years, from the bucolic South Downs of A Mere Accident and Spring Days to the urban contest of Esther Waters, except to note that there was a segue: Esther Waters opened in a fictional version of the Bridger home, Buckingham House.

In my view, the most plausible explanation of George’s rise from A Mere Accident and Spring Days to Esther Waters (by way of Mike Fletcher and Vain Fortune) may be found the old saw: he pulled himself up by his bootstraps.

His ability to do that again and again over the course of his career is probably what endeared him most to fans like me. George was an experimentalist and, like a lab scientist, his failures were as numerous as his successes; even more numerous (maybe)!

Somehow he was not deflated or discouraged when he missed his mark. Like Samuel Beckett in another generation, he concluded with “I’ll go on.” Or to put that in George’s words:

I shivered; the cold air of morning blew in my face, I closed the window, and sitting at the table, haggard and overworn, I continued my novel.

Confessions of a Young Man (1888), page 357

Next Up

Letters from 1894-1895 will be next up in the Letters pillar of this website.

By the way, thousands of George Moore’s letters are preserved in known institutional libraries, but an unknown number of others are in private collections. For example, I own a few MSS.

Privately owned letters have turned up over the years in bookseller catalogs, but not otherwise found. I have not figured out how to track them down in the digital age, but my intuition is that there is an efficient way. Suggestions are welcome!

The novel Mike Fletcher (1889), another miss for George, will be next up in the Worlds pillar of this website and the GMi Shop. I first read it a long time ago and have zero memory of it now. Bracing myself!