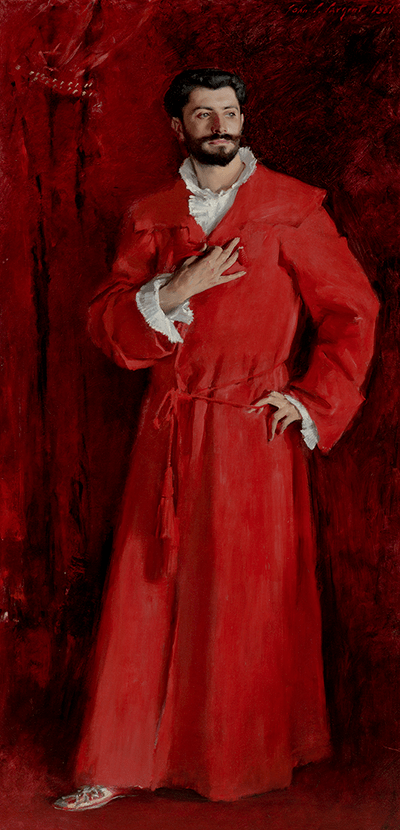

A Woman Playing a Clavichord (c. 1665), oil on panel by Gerrit Dou, in the Dulwich Picture Gallery (Wikimedia Commons). In a scene that takes place at the Gallery in chapter 4 of Evelyn Innes (1898), this painting foreshadows the drama that will unfold over the next 400 pages: “‘Ah! she’s playing a virginal!’ said Evelyn, suddenly. ‘She is like me, playing and thinking of other things. You can see she is not thinking of the music. She is thinking… she is thinking of the world outside.’” Virginals were among the instruments that Evelyn’s father made and repaired in his home studio. Though similar to clavichords, George mistook the keyboard in the painting for a virginal because, when he wrote his novel, the painting was named A Lady playing the Virginals in the catalog of the Dulwich Picture Gallery. The stringed instrument behind the lady is a viola da gamba, like the one Evelyn played in her father’s concerts of old music, before she left home for a singing career in grand opera.

Renegade Catholic?

George Moore’s first publication was a volume of decadent, sacrilegious poetry named Flowers of Passion (1878). His third was a similar volume named Pagan Poems (1881).

Did a vainglorious apostate write those unseemly books? Judging by their contents, it would seem so, except that his second book — oddly sandwiched between his botanic paganism — was Martin Luther (1879), a respectful (if juvenile) five-act play honoring the Catholic priest who kickstarted the Protestant Reformation.

Throughout his long career, George continued writing novels, essays and plays that were tethered to religious, or at least spiritual loss and aspiration. An apotheosis of that lifelong project was the reimagined Jesus Christ in his novel, The Brook Kerith (1916), in which the Savior didn’t die for us but thoughtfully evolved into a flaming heretic!

By birth and upbringing, George was Irish Catholic, though evidently never comfortable with that conflicted ethnographic label (nor its Western partner, Irish Landed Gentry).

Depending on the focus of his ire or inspiration, by his own choice he may have been (or at least pretended he was) a pinball apostate, heretic, iconoclast, agnostic. With a performative conversion to the Anglican faith in middle age, he grabbed the fresh label of Protestant, but was he ever?

It is tempting to reject Protestant and all his other labels as useless; all except two: contrarian and secular humanist. He was temperamentally pious but ornery, variable and inconsistent as a religious believer and practitioner. It’s still hard for me to pin him down or make him adhere to any dogma for longer than it takes for the weather to change.

For sure, though, from end to end of his literary odyssey, he vigorously and gleefully, albeit quixotically, attacked the Roman Catholic Church as a decrepit, dysfunctional windmill.

Except when he didn’t. For example, Evelyn Innes was, according to me at least, a Catholic novel. Despite filippant criticism that condemned it as disgusting (because of amorous details), his tome is nothing less than reverential. The protagonist is a prodigal Catholic Englishwoman who returns to her mother Church in an ecstasy of hope and renewed obedience.

Setting aside the question “Why did George write it?” and not looking ahead to the sequel Sister Teresa (1901), in my opinion the author of Evelyn Innes was indeed a renegade Catholic, but one who engaged again and again with tenets of a Church that he scorned but couldn’t get out of his system.

“I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.” So wrote the Catholic Ernest Dowson in a poem published the year George began writing Evelyn Innes. Dowson insisted again and again: “I was desolate and sick of an old passion,” and that is precisely how George felt as he neared the finish line of his long novel four years after starting it. In February 1898, he wrote in a letter to Lady Cunard:

I send you the proofs — I fancy that they are about a third of the book. I am feeling so depressed that I cannot come to tea; you would only think me hateful. Do you know what a black melancholy is? If there was only a reason but it is the sorrow of life, the primal sorrow. This sounds melodramatic, exaggerated, pedantic… Indifferent as the fiction doubtless is it is better than the horrible reality known as George Moore

His mood in the runup to publication of Evelyn Innes mirrored Evelyn’s before her confession to Monsignor Mostyn. She returned to the Church in her late 20s to settle her conscience.

George in his late 40s, after tilting at sundry windmills, may have considered doing something similar, but ultimately chose to remain a renegade, much like that woman playing a clavichord, “thinking of the world outside.“

Textual Conundrum

The first edition of Evelyn Innes is live on GMi — in three forms for different uses.

- 35 transcribed and lightly edited chapters for close scrutiny

- A PDF for guided analysis and interpretation in an AI app

- A free ebook for people who quaintly still read for pleasure

My custom of publishing first editions of George Moore’s works (22 and counting) sailed into choppy waters this month because several versions of Evelyn Innes technically vied for that singular rank.

Chronologically, an American edition was the first to market, but since it was expurgated by the publisher’s (Appleton’s) editor (George William Sheldon) — with George Moore’s consent but not cooperation — I chose to disregard it.

Instead I published the first English edition, which came out a few days later. At more than 180,000 words it was George’s biggest book to date.

I didn’t know ahead of time that he crammed so much writing into 480 printed pages. Editing on a deadline, so to speak, I got a little annoyed by the time I was taking to get through it all.

Did Evelyn Innes have to be so long? Certainly there are problems that George’s editor, if he had one he trusted (he didn’t), could have helped him avoid.

Foremost was pacing. He ever so slowly unpacked his idea of the novel, partly because of redundancies (saying pretty much the same thing again and again) and partly because of digressions.

The most tedious digressions (to me) were musical. George had a lot to say about the modern music of Richard Wagner and ancient music of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, not all of it (dare I say) germane to his plot.

I am not the right person to object to his digressive content, since I don’t enjoy Wagner’s operas or Palestrina’s chorals. If I did, I probably would have forgiven George his hobbyhorses as he went off the literary rails into classical musicology. It’s not germane, but it isn’t irrelevant either!

Annoyed or not, I have published the book George wrote, though my choice of edition was further complicated.

Even before the publication of his first English edition in June 1898, George messed with his text a lot and concluded the book was hopelessly flawed. The first edition of 10,000 copies sold briskly despite his reservations, and that gave him the opportunity to spend a lot of his and his publisher’s money on revisions for a second edition in August 1898.

Because the second edition represented his considered intentions at the time of original publication, I wondered if I should break with custom and choose it for GMi. I almost did, but then remembered another “trial revised edition” (i.e. a third edition) was even closer to his intentions at the time.

This moving target of versions started to matter more when I remembered that Evelyn Innes is only part one of a duology. Part two was unwritten in 1898. It followed in 1901 under the title of Sister Teresa (the religious name of the same leading protagonist). Which of the three versions of Evelyn Innes in 1898 would sync with Sister Teresa in 1901?

The answer is: none. Instead, a formally designated third edition of Evelyn Innes in 1901 (in reality, the fourth edition) would embody the trial revised edition of 1898 with even more changes added.

That third (fourth) is the version of Evelyn Innes that syncs properly with Sister Teresa. The third (fourth) edition of part one and the first edition of part two of the duology may be regarded as the first complete state of the author’s intended and finished work.

The takeaway of this? The Evelyn Innes now published by GMi is a kind of first edition, though it lacks the distinction of representing the author’s original idea. He just wasn’t finished telling his story when Evelyn Innes came out. He didn’t finish until three years later.

That leaves me with a quandary. When I publish Sister Teresa, should I also publish the third (fourth) edition of Evelyn Innes so that we can draw a line under the title and call it a day?

I haven’t decided. Remember, I was annoyed by the length of Evelyn Innes in getting even this far. I’m not sure I want to go through the grinding editorial mill again.

Keep the Faith

Evelyn Innes was George Moore’s ninth novel and eighteenth book. In more ways than one, this wasn’t his first rodeo.

Evelyn’s prototype was Kate Ede, the housewife in A Mummer’s Wife (1885) who left her husband for Dick Lennox, just as Evelyn would leave her father for Owen Asher. Both women were rather homely but enchanted by the theater; both had paramours who offered them glamour and success on the stage; both enjoyed steamy sexual relations with their main squeeze; both were almost saved by the virtuous friendship of an opera composer (Kate’s was Montgomerie, Evelyn’s was Ulick Dean); and both ultimately suffered a nervous breakdown that ended their careers and love affairs.

Why a nervous breakdown?

The answer was succinctly put in Book 3 Chapter 1 of A Drama in Muslin (1886) when Alice Barton tried to explain her humane morality to the waspish Cecila Cullen. Alice struggled to find the right words, so her creator spoke up on her behalf: “the ideal life should lie… in making the two ends meet — in making the ends of nature the ends also of what we call our conscience.”

In A Mummer’s Wife, the simple-minded Kate sought refuge from her guilty conscience in alcohol. The protagonist of Evelyn Innes, though equally carnal, was anything but simple-minded. She sought refuge in a more elaborate and constructive kind of oblivion: the Catholic Church.

If the penitent accepted the Church as the true Church, conscience was laid aside for doctrine. The value of the Church was that it relieved the individual of the responsibility of life. (Evelyn Innes, Chapter 34)

Evelyn’s triumphs on the stage did not ameliorate a growing conviction (like Kate’s) that she was depraved. She had made a Mephistophelean bargain to exchange her deep-rooted religious values and identity for professional growth, worldly success, and sexual fulfillment.

Over the course of six years, the bargain drove her crazy and proved unsustainable. Like Kate Ede, Evelyn Innes plunged into acute depression.

But again the music stirred her memory like wind the tall grasses, and out of the slowly-moving harmonies there arose an invocation of the strange pathos of existence; no plaint for an accidental sorrow, something that happened to you or me, or might have happened, if our circumstances had been different; only the mood of desolate self-consciousness in which the soul slowly contemplates the disaster of existence. The melancholy that the music exhales is no querulous feminine plaint, but an immemorial melancholy, an exalted resignation. (Evelyn Innes, Chapter 35)

Lucidly echoing his protagonist’s existential howl, bitterly reflecting on the novel’s blunt-force critical reception soon after it was published, the dejected modernist author confided in a letter to his friend Edmund Gosse: “I have composed my epitaph: He discovered his own limitations and the limitless stupidity of the world.”

Of course this being George, he didn’t walk away from the project or his inner struggle. He took up the pen and resumed writing the sequel in a state of “exalted resignation,” previewing the mood of the next hapless century:

Where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on. (Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable (1953)

George’s Letters

October was a busy month at GMi. In addition to publishing Evelyn Innes, I transcribed, edited and annotated the letters of 1898.

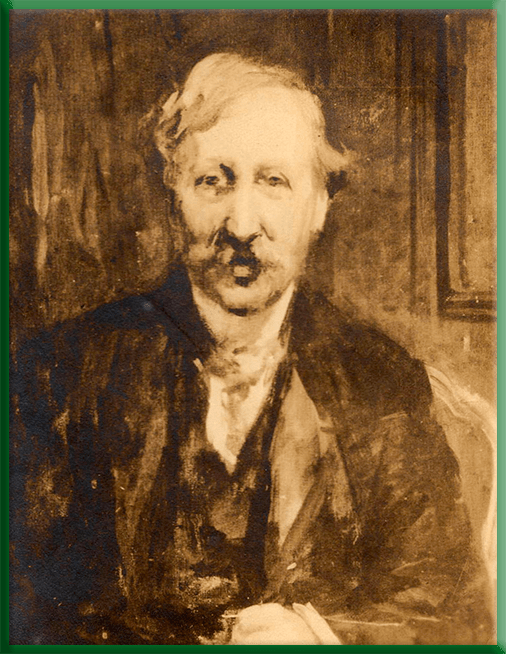

George was 46 years old in that year, unmarried but a father (according to me), renting a large flat in Victoria Street, London, making a comfortable living from his pen, and exercising mature literary powers though far from the acme of his career.

His friendship with the poet William Butler Yeats blossomed in 1898. Yeats was the model for the character of Ulick Dean in Evelyn Innes; moreover he profoundly influenced George’s aesthetics, craft, and politics, surprisingly drawing him beyond English liberalism into fervent Irish nationalism.

When the duology of Evelyn Innes and Sister Teresa was finished in 1901, George repatriated to Ireland.

Next Up

For the first time since launching George Moore Interactive, I’m about to take a mini sabbatical. November 2025 will be devoted to Resurgam, the not-for-profit corporation that raises funds for GMi and similar causes.

Resurgam has qualified several grant-makers who are chartered to support this work. During my sabbatical, I will shortlist the most promising prospects and help Resurgam prepare competitive grant applications.

When I return to GMi in December, George Moore’s letters of 1899 will go on the workbench, along with his novel Sister Teresa. See you then!