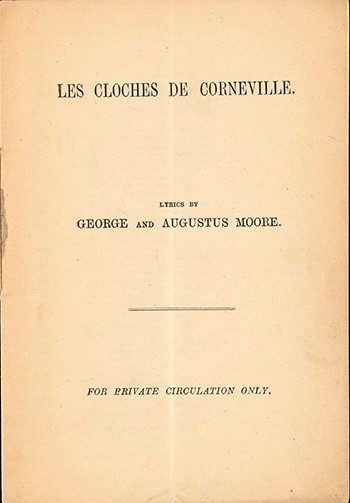

The title page of Les Cloches de Corneville, a translation by George Moore and his younger brother Augustus, of lyrics by Louis Claireville for Robert Planquette’s comic opera. The show opened in London on 29 March 1883 at the Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques — named after an historic theater in Paris where Les Cloches premiered in 1877. George was living in Paris at that time and doubtless saw it. This 24-page libretto is one of the rarest of Moore first editions; only this copy is extant, preserved at the Arizona State University Library. Though it’s a translation, a product of collaboration, and an adaptation of another author’s work, it is nonetheless part of George Moore’s canon and an early instance of his worldbuilding.

Volume A45 in A Bibliography of George Moore is a lump of literary flotsam: the unauthorized printing in 1923 or 1924 of ephemera that Edwin Gilcher called Insert for Memoirs of My Dead Life.

The purported “Insert” is variant text for a volume of autobiographical stories that Moore published in 1906. Here is Edwin’s description (cluttered with my bracketed edits):

An unauthorized printing of a discarded draft [manuscript] of material added to the Tauchnitz edition of Memoirs of My Dead Life (A29-b), beginning as that does, but developing quite differently. The two versions [of the story] are both quoted by Rupert Hart-Davis, in tracing GM’s relationship to Lady Cunard, in the “Introduction” to [George Moore] Letters to Lady Cunard (A65).

GM was unaware of this [unauthorized] printing and first learned of it about 1930 when he was shown a copy by [bibliophile] Frank [Hix] Fayant [whose collection is now at Cornell University Library].

Previously [bibliophile, publisher and biographer] A.J.A. Symons had requested permission to have the [manuscript] fragment printed, but in a letter dated “3rd March, 1926” GM refused, saying “These pages were stolen by one of my secretaries and sold, I think in America… I should be very sorry indeed to see these pages published.”

The original manuscript was listed in the 1913 Christmas Catalogue of C.W. Beaumont, London; was later sold at auction in the United States; and is now in the collection of Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., of New York.

A Bibliography of George Moore (1970), pages 117-118

I have gathered digital scans of first editions of all George Moore’s creative writing for the Worlds pillar of this project. This particularly rare item was my final quarry. I was pretty close when I learned that a copy was auctioned at Sotheby’s (London) in 2007, but still haven’t gotten my hands on it.

That being said, I have cornered something just as good — maybe better.

Unable to trace Insert for Memoirs of My Dead Life with an Internet search, I decided to follow the clue of “Arthur A. Houghton, Jr., of New York.” If I can’t find that unauthorized printing, I reasoned, maybe I can find the manuscript it was based on.

I learned that Mr. Houghton, son of a president of Corning Glass, was the long-time head of its Steuben Glass subsidiary. He was a man of rare business and aesthetic acumen, and also quite the bibliophile. While running Steuben he served as a curator of rare books at the United States Library of Congress, in his spare time. I would enjoy meeting him for sure, but he died in 1990.

Donning my deerstalker hat, I soon discovered that some of Mr. Houghton’s personal library was auctioned at Christie’s (London) in 1979. In response to inquiry, a gracious person in the their department of Books, Manuscripts and Scientific Instruments identified the buyer of Moore’s manuscript at that auction more than forty years ago.

Eureka — almost, because the buyer of Moore’s manuscript was a New York bookseller who is now deceased and whose business is no more. Oh no!

The thing about a deerstalker is that it doesn’t let a wearer give up too soon; it wants to be lived up to, and that’s why Sherlock and I like it. With more snooping I discovered that the late bookseller’s business records had long ago been donated to the Grolier Club, also in New York. But were these records precise enough to identify the next owner of the vagrant manuscript?

Turns out the records are splendid! A gracious librarian at the Grolier Club investigated and found that Moore’s manuscript, previously owned by Mr. Houghton, was bought by the (now deceased) bookseller on behalf of the Morgan Library in New York. And that is where the manuscript is today.

I ordered a digital scan for the Worlds pillar. Ergo I have now acquired digital files of every first version of all George Moore’s creative writing!

So what? Glad you asked.

The complete digital archive allows me to convert all of Moore’s creative writing into Google Docs, where I can render it fit for automated textual analysis and machine learning.

An anticipated outcome of this process is groundbreaking insight into the worldbuilding prowess of novelist, playwright and poet George Moore. His semantic, semiotic and stylistic patterns and conventions will emerge from the permafrost of printed paper into the flesh-and-bones of active text with behavioral properties.

All good, and yet, if you had the patience to read my lecture on Kick-Starting Literary Legacies, you know that the endgame of this project is still more ambitious. I’m not about making research tools for investigators; that’s just a by-product.

My inspired goal is to reanimate George Moore with generative artificial intelligence, so that any reader can interrogate the author himself about the books he dreamed up and wrote. Folks like me want to experience books we love to the max, and that calls for rocket-powered lift off from the printed and electronic page. Start the countdown!

The raw data that constitute Moore’s legacy of worldbuilding inform the Worlds pillar of this project. All of them are now in the hopper, ready to be rendered elegantly.

A.O. Scott Redux

In a recent post, I linked to A.O. Scott’s article about D.H. Lawrence’s rare gift for literary criticism. By coincidence, I later heard David Runciman’s podcast Past Present Future about Susan Sontag’s essay Against Criticism. Sontag was very much to the point I was making in Critical Heritage.

Professor Runciman actually mentioned another A.O. Scott article in the New York Times: “How Susan Sontag Taught Me to Think,” and now I’m passing that on to you as well.

I’d like you to listen to the Runciman podcast and read the Scott article and the Sontag essay. No, this is not homework for George Moore Interactive; there won’t be a quiz. I want you to do this only because it may enhance your appreciation of George Moore more than scholarly articles do.

A.O. Scott tells us: Some writers supply the solid virtues of a husband: reliability, intelligibility, generosity, decency. There are other writers in whom one prizes the gifts of a lover, gifts of temperament rather than of moral goodness. Notoriously, women tolerate qualities in a lover — moodiness, selfishness, unreliability, brutality — that they would never countenance in a husband, in return for excitement, an infusion of intense feeling. In the same way, readers put up with unintelligibility, obsessiveness, painful truths, lies, bad grammar — if, in compensation, the writer allows them to savor rare emotions and dangerous sensations.

That is precisely what George Moore endeavored to do long before Scott and Sontag and Runciman arrived to explain it. I gather that Sontag read Moore early on, though it seems she read everything; I can’t say that either Scott or Runciman have, but I hope someday they will.

Contrarian George

Speaking of critical heritage, I continue my remedial reading of scholarly articles about George Moore that were published while I was busy elsewhere. Last week I stumbled upon one such article that was written by me. Surprise!

I like that my article viewed Moore in rapport with popular culture. I haven’t come across others with that perspective; by contrast they are innately of the Ivory Tower, whereas my drivel is a bit more down to earth.

That may be a weakness rather than a strength, but anyway I spent a few hours editing my years-old text so that it sounds like me today more or less. The revised version is a new page on this blog.

Help Wanted

George Moore Interactive is a solo performance at present, but eventually I’ll want helpers. Employees, contractors, vendors, or altruistic volunteers? All of the above — depends on who’s available.

One quickly emerging need is a careful proofreader who knows or can learn how bibliographies of literature are written and read. The proofreader who joins GMi will scrutinize my docs and try to perfect them.

Caveat: the work pays very little or nothing at all, but it’s engrossing and fun. Ideal for dreary winter months when your garden is napping.

Breaking News

I recently incorporated George Moore Interactive LLC, an administrative step that supports my planned growth.

I also registered two new domains for a total of three. All are named georgemooreinteractive plus an extension:

- .blog for news and views of the project

- .org for free content in the seven pillars

- .info for paid content in the seven pillars

The websites of these domains will look similar and work synchronously. Movement between them will be frictionless depending on how they’re visited:

- Anonymously — free and limited

- As a subscriber — free with personalization and limited

- As a member — paid with personalization and unlimited

You can pop over to .org by tapping the GMi logo at the top of this page. A similar button over there will bring you right back.

These architectural developments should make the experience of George Moore Interactive pleasing and edifying for lots of people, while setting a higher bar for how to engage with literary legacies in the digital age.