Love for Sale

Shelves in the GMi Shop are (awkwardly) kinda bare. Remember though, a shingle was hung only yesterday!

But check this out: a few things are now in the shop window: e-books of Martin Luther (1879), A Mummer’s Wife (1885), Avowals (1919), and Conversations in Ebury Street (1924). Each is edited by me, contains the text of the first English edition, and costs about the same as a cup of morning joe.

What? that’s too expensive? I agree, the price really should be free, but for structural reasons I can’t give titles away in the Kindle Store. Instead I do that in George Moore Interactive. The contents of these e-books are published hereabouts in the Aesthetics and Worlds pillars, for free.

The dual publications are not duplicative. Readers who want to enjoy Moore’s writing will do that better with Kindle editions. Those digital texts are faithful to the printed originals; moreover they aren’t cluttered with new introductions that tend, in my experience, to prevent the average reader from enjoying what follows.

Instead of opening with a pooh-bah’s footnoted explanation of what the book means to him or her or them, readers of these e-books dive in and decide what it actually means to themselves. An experience of engagement and discovery, lofted by canonical text, is attainable.

This is partly what I mean when I talk about “kickstarting literary legacies in the digital age.” Empowering everyday readers to read what and how they want, primarily for the sake of personal enjoyment rather than edification. I am guided here by (George) Moore’s Law that “education is of no help to anybody except teachers” (see Chapter 17, Conversations in Ebury Street).

Yet there is more than enjoyment to reading in the digital age.

Readers who also want to scrutinize and interrogate the canon, and explore its larger historical context, will do that better on the GMi website. Here they can see what Moore was working on before and after each of his books came out. Here they can search his texts for keywords in order to find and connect dots of particular interest to themselves (and the author).

They can even share their thoughts by attaching questions and comments to canonical writing for fellow readers to ponder and discuss. And they can view pictures of their author around the time he wrote; of people who turn up in his writings; and of places where he wrote. For an immersive experience of the “life and work.”

Of greater importance to me (text maven that I am), they can point out errors in my transcriptions of the canon — typos, formatting — that I may correct and thus make better for readers who come after. (I say may correct because some errors appear to be intentional and self-expressive; beyond my reach.)

Readers can do all of those sticky things on the GMi website. I have also unlocked the gates to GMi stacks in the cloud where all of my transcripts and scans of printed and handwritten texts are filed. Unlocking the gates allows readers to search the canon globally, rather than one document at a time.

You can tell if you glanced at my uniform e-book cover design, my goal is to publish the entire GM canon in George Moore Interactive and the Kindle Store. That way, when future visitors to the website converse with the great man himself (AI generated), and he says something intriguing or puzzling (true to form), they can follow up by seeing just where he was coming from. Instantly and for free!

Next up for digital kickstart: Confessions of a Young Man. This remarkable expat memoir of 1888 (the author was 36) is the first (to my knowledge) Irish portrait of the artist as a young man. James Joyce followed some 30 years later (when he was 34) with the second.

Stochastic Dialogue

Creative writings like plays (Martin Luther) and novels (A Mummer’s Wife) are internally all of a piece. Their linear narratives are bookended by opening and closing acts; and their mass — from 20,000 to 150,000 words — is all one thing, date-stamped on the day of publication.

Critical writings are different. Avowals and Conversations in Ebury Street are nonlinear; their various chapters are discrete essays in art criticism, literary criticism, and worldbuilding; most are in English, one is in French, several are generously endowed with French interpolations; some essays were previously published in periodicals, others appeared for the first time in hardcover; but all were ultimately arranged in no discernible order.

The essays may be read in any order; their published sequence is neither chronological nor prescriptive and does nothing to enhance the meaning or coherence of each one. In effect, the placement is random.

GMi Kindle editions of Avowals and Conversations in Ebury Street preserve the placement of essays in the printed books. Not so the pillars of George Moore Interactive, where each essay is handled as separate document (what it is, in fact).

The rhetorical format of some essays in Conversation in Ebury Street is (as you’d expect) a dialogue between people. What you might not expect, given the book title, is that some essays are not dialogues, but straightforward articles.

Same goes for Avowals, which also veers from the straight and narrow path implied by its title into the format of dialogue or a lecture written entirely in French (years before revised publication in this book).

The bottom line is this: like much of George Moore’s writing, these two books of criticism don’t follow any rules. What they have in common are contrarian principles of self-expression and open aesthetic inquiry.

The essays are “all over the place” yet somehow present in the moment, and always “wholly and irreparably given to art” as Moore wrote about himself. They are confessional, yes, for sure; and also meandering like a conversation you would enjoy with an old friend in the garden or in front of a fire.

French agon

“Shakespeare et Balzac” is the lecture in French that appears as Chapter 13 of Avowals. A bit challenging for me to transcribe with the French alphabet, but a walk in the park compared to another essay that I recently published in the Aesthetics pillar: “Le Poète Anglais Shelley.”

I obtained a human-readable scan of this 1886 article from RetroNews, but since it was not machine-readable, I had to type all 3,200 French words. This was a bona fide agon between my old and young selves.

I think I got it right for the most part. If a French-fluent volunteer wishes to check my transcript for errors and send me corrections, I will be more than a little grateful. Step up on the Volunteer page of the GMi website.

At Le Val Changis

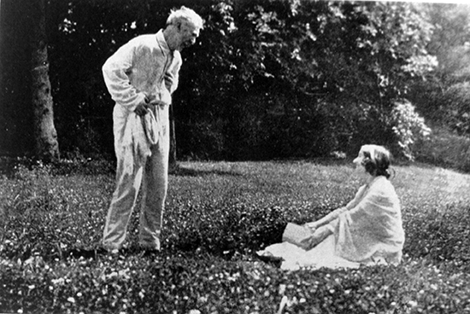

Speaking of context, years ago I visited the elderly Marie Dujardin at her home in a suburb of Paris. She is the unnamed young woman pictured in Joseph Hone’s The Life of George Moore (facing page 400):

She was previously mentioned in Chapter 14 of Conversations in Ebury Street; that chapter was George’s impressionist memoir of Le Val Changis, the home of Marie’s much older husband Édouard Dujardin. The memoir evokes the splendor and charm of the place, where George was an annual guest for several years.

Before my visit ended, Mme. Dujardin pulled a box from under her bed and retrieved the photograph that I placed at the top of this post. I call it Les lauriers sont coupés for obvious reasons. I asked Marie what George was like, as a friend and fellow writer and houseguest, and she answered with only one word: égoïste.

I can relate…

My personal fondness for George began in the early 1970s when Professor Warren Herendeen at New York University told me to read Esther Waters. I was already fascinated by modernism, without even knowing what it was; and this novel, by this author, seemed like the acme of that “transitional” movement.

A few years later, after earning my PhD in England with research on the letters of Moore, and after a postdoc and stints of undergraduate teaching, I decided to leave academia for a lot of good reasons, which we won’t go into. My work on GM ceased and I became just a collector.

Sure as I was and am about the wisdom of that decision, now that I am back in a wholehearted quest for George Moore, I am reliving the fascination that hooked me at the beginning. And thinking about roads not taken, as one should from time to time.

All of this is preamble to a quote I stumbled upon in Chapter 8 of Conversations in Ebury Street, a quote that illustrates a point I like to make about this project: that George Moore is a major writer whose legacy has much, very much to offer readers today.

In this quote he describes himself pivoting from a first choice of career to a second. He did not regret it, he did not second-guess it, but he acknowledged that the experience helped to make the man he became:

A man who leaves his profession faces the world naked and ashamed — ashamed because to leave the road he has chosen to walk in is a confession of failure, naked because he has to put off the old man (exact knowledge), and live henceforth amid ecstasies, dreams, aspirations; humble aspirations, mayhap, but aspirations after all. Think, reader, what a shock it is for a man to leave one self without knowing that he can acquire another self. I shed tears, and the bitterest.