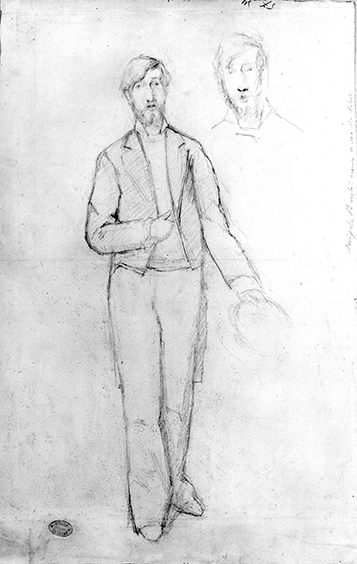

George Moore in his late twenties (circa 1879-1881), looking much like he does in engravings by Mary Cassatt around 1880. A second head is drawn in the upper right. The sketch is graphite on paper, undated, unsigned, stamped “Atelier Ed. Degas” in the lower left. The sketch was carefully attributed to Edgar Degas by art historian Ronald Pickvance; later it was deemed a forgery by another art historian Theodore Reff. The owner of the picture, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, sides with Reff. I find Pickvance far more convincing; moreover I can’t easily imagine a forger laboring over this subject in this medium with this result. That seems absurd. I call the picture Le Dandy des Batignolles, one of Moore’s nicknames in the 1870s according to the artist Jacques-Émile Blanche, who also painted Moore (at least twice). This picture is not in the Manet/Degas exhibition in New York.

Tell ‘em what your gonna tell ‘em. Then tell ‘em. Then tell ‘em what you just told ‘em. This pearly wisdom purportedly comes to us courtesy of the Rev. John Henry Jowett in “Three Parts of a Sermon,” his advice to preachers in the Northern Daily Mail of Durham, England sometime in 1908.

I mention it here because I’m going to share something about George Moore Interactive that I’ve said before, but it probably didn’t stick. So my first pass was episode one of a Jowett clincher; today’s post is episode two; and at some later time I’ll return with episode three. That settles it!

My “tell” concerns the technical platform of GMi. A platform that stretches across three separate but interrelated domains. All three begin with georgemooreinteractive and what follows makes each one unique:

- .blog is where you are now, for news and views of this project

- .org is where the seven pillars of George Moore’s legacy are published

- .info is where people grok a realistic George in immersive simulations

At the top of every page and post in .blog (including this one), there’s a GMi logo button you can click or tap and be instantly transported to .org. When there, at the top of every page in .org there’s a different logo button you can click or tap and pop over to .blog. Go ahead and try it if you’re curious.

That second logo button is from a portrait of George Moore painted by Philip Wilson Steer, just so you know. Nowhere on .blog or .org will you find a link to .info, because that registered domain doesn’t have a website. Yet. It’s the beachhead for George’s reanimation, a mystery wrapped in enigma, a wondrous confection of neural networking “coming soon to a screen near you.”

Now then, having completed the second episode of a Jowett clincher with that explanation, I can share the new news. Since my last post, .org has launched and is growing fairly quickly. As of today it has 470 web pages forming two of the seven pillars of GMi: Aesthetics and Bibliography.

Most of George Moore’s art criticism is now live in the Aesthetics pillar of .org. I’m still yanking the last 20 essays out of their analog coffins (i.e. newspaper libraries). Not fun, not cheap, but doable if I don’t lose my temper and throw french fries at the wall.

Art criticism used to be the entire purview of Aesthetics, but I realize now that it’s not enough. So I’m also gathering George’s literary criticism for that pillar, but not before all the art criticism is online.

In the Bibliography pillar of .org, the text of Edwin Gilcher’s two books are live: unified, reformatted for online viewing, and about to be proofread by a gracious volunteer. I tried to get it right but doubtless there are wrinkles to iron out. Nonetheless, Edwin’s remarkable legacy has crossed the chasm into the twenty-first century!

All the essays in Aesthetics, and all the entries in Bibliography, are in Google Docs. When you open most .org web pages, you’ll see a white box filled with a scrolling Google Doc. You don’t have to go elsewhere for the text, it’s free and easy to read, right in front of you where it should be.

Now comes a very, very important point. I talk a lot about kickstarting literary legacies in the digital age. What that means, among other things, is making them participatory. Making it possible for people like you to become involved with a legacy; in particular to enhance it by finding and reporting issues.

What kinds of issues? Typographical errors, erroneous facts, incoherent descriptions, incomplete data. A participatory literary legacy is one in which individuals can share their questions and suggestions, and continuously build on what we have and know.

The way they participate is to post comments on the web pages themselves. That’s handy for issues specific to a page. Alternatively they can use a Contact web form for issues that are site-wide and have to do with general strategy and design.

A third mode of participation is behaving, for the moment, like a breech baby; like it doesn’t want to come out and play. In this third mode, individuals add comments to words and lines of George’s writing, so the precise location of an issue is marked and targeted. Thankfully I have two ways to flip that baby into the birth canal. The best way is the one I want, so I’m spending extra time on it, but the second way will also work, so that’s plan b.

As George’s legacy slides into the digital age, keep in mind that .org and later .info are “minimum viable products.” They’re unfinished, rough cuts, tips of the digital iceberg. By making a legacy participatory, I’m encouraging everybody to become active readers, makers and co-creators.

So yes, please do curl up with a book or an e-reader in front of the fireplace during the cold winter months; but also, when you notice something, such as a book by George that is not in his bibliography, go straight to your computer and share that fact with our community. Participate!

Manet/Degas

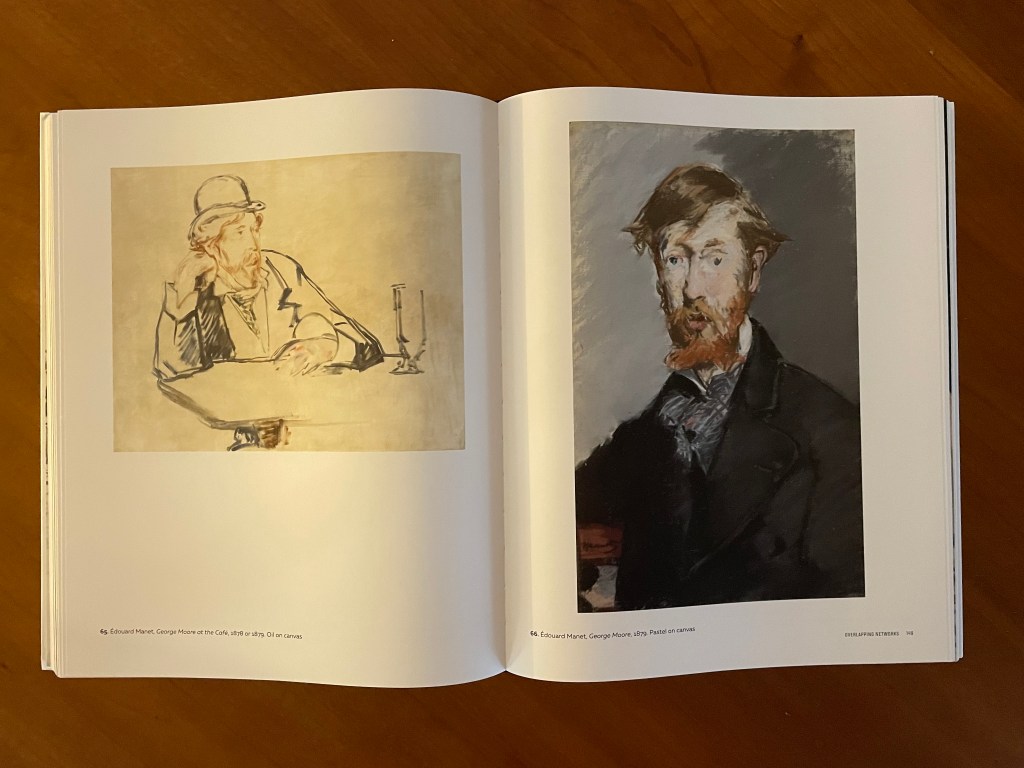

The catalog of the Manet/Degas exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has published. It’s a gorgeous big book that belongs on your coffee table. On pages 148-149 you’ll find two of George’s portraits by Manet (plates 65-66), dated 1878 and 1879, both in the permanent collection of the Met. A third such portrait is in Washington DC and a purported fourth is in Boston. They’re not in this exhibition but they are in the GMi Iconography.

(Viewers of the new season of Lupin may recognize the picture on the left. It appears on screen for about a quarter of a second, while Assane Diop puts a stolen Manet painting in his crosshairs.)

Speaking of a Launch

A new book of scholarly essays, entitled George Moore: Spheres of Influence, has been published in the UK and can be ordered on Amazon here in the USA. Wait a while and it may show up at a library near you. I attended the online launch party a few days ago, where several of the contributors formed a shimmering coterie. If conscientious dedication to the Sage of Ebury Street can persuade general readers to take him up, then these assiduous scholars, and their students, will be the ones doing it.